On this day in 1916 (August 16 old calendar / August 29 new calendar), Lieutenant Colonel Konstantinos Mazarakis-Ainian tried to seize control of an artillery battalion in Thessaloniki. His effort was quickly put down, but it showed that the Greek army was no longer united. That failed attempt became the trigger for the National Defence coup d’état, which broke out the following day (August 17 old calendar / August 30 new calendar) when pro-Venizelist officers pressed ahead and openly rebelled.

The background was already tense. Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos wanted Greece to join the Allies in the Great War. King Constantine I, bound by marriage to Kaiser Wilhelm’s sister, insisted on neutrality. What began in 1915 as a bitter disagreement over foreign policy had grown into something larger. Greeks spoke of the National Schism (Εθνικός διχασμός), a divide that split families, villages, and even army regiments.

The day after Mazarakis-Ainian’s failed move, pro-Venizelist officers in Thessaloniki pushed forward and formed the Committee of National Defence, with quiet encouragement from French and British officers stationed there. At first, Venizelos himself disapproved, fearing the revolt was premature.

But as Bulgaria advanced in Macedonia and the crisis deepened, he decided to align with the movement. Within weeks he set up a Provisional Government of National Defence in Thessaloniki, while King Constantine continued to rule in Athens. Greece now had two governments, two armies, and two competing visions of its future.

The standoff was not resolved until June 1917, when the Allies forced Constantine into exile and restored Venizelos to power. Greece entered the war on the side of the Allies, and its troops fought with distinction on the Macedonian Front.

Yet the National Schism did not end there. It remained a deep wound that shaped Greek politics for decades. It divided parties, poisoned elections, and resurfaced during the Asia Minor Campaign, the Asia Minor Catastrophe (Μικρασιατική καταστροφή) of 1922, and well beyond.

For Greeks abroad, the consequences were just as real. Thousands of young immigrants in America had already returned to fight in the Balkan Wars, and many went back again during the First World War and the Asia Minor Campaign. When the Catastrophe forced more than a million people from Smyrna, Pontos, Constantinople, Eastern Thrace, and other parts of Asia Minor into exile, some found homes in Greece while others crossed the Atlantic. Cities like Boston, Philadelphia, New York, and Chicago grew with new arrivals who carried the foods, songs, and stories of their lost homelands, reshaping Greek-American life.

Seen in that light, the events of August 29 and 30 were more than a coup in Thessaloniki. They were the moment when the National Schism turned from political dispute to armed revolt, a turning point that reshaped Greece itself and also sent shockwaves across the seas. Out of that division came war, displacement, and migration, forces that helped shape not only modern Greece but also Greek communities around the world. And the legacy of the National Schism did not end in 1922. Its divisions echoed through Greek politics for decades, resurfacing in the turmoil of the Second World War and again in the Civil War that followed.

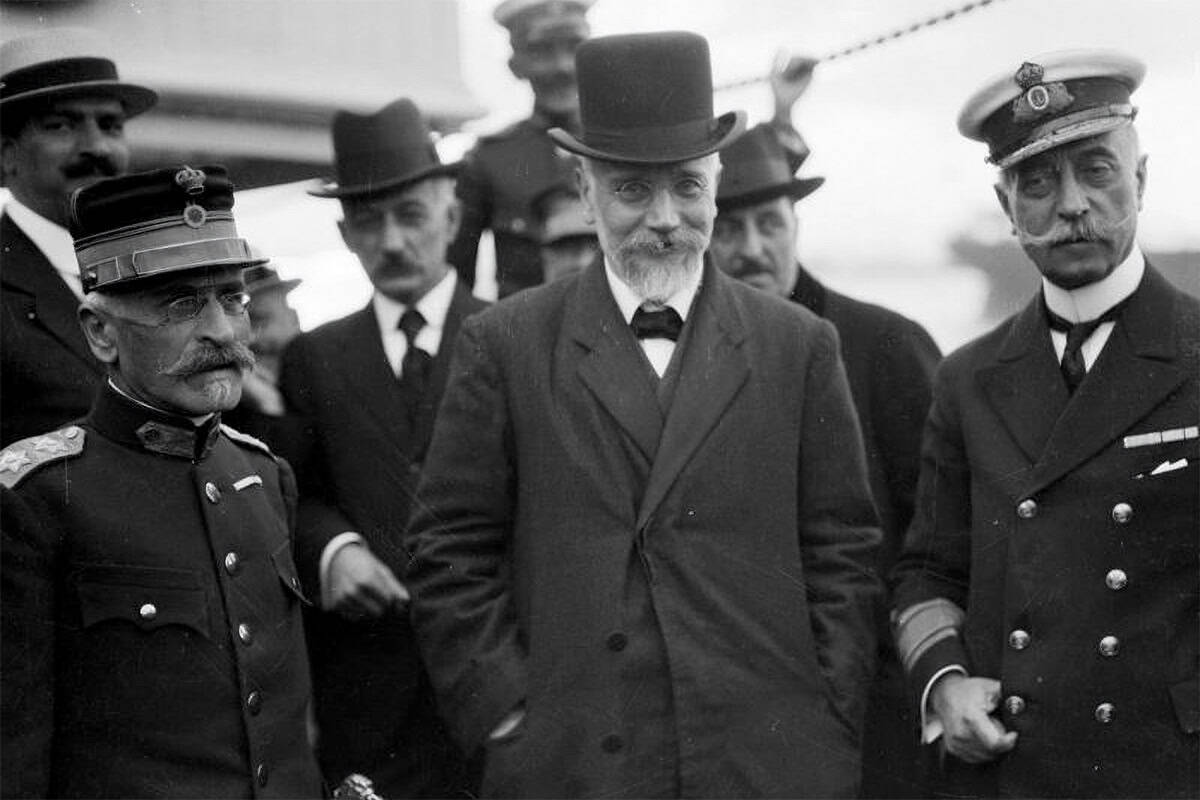

Featured image: Eleftherios Venizelos with General Panagiotis Danglis and Admiral Pavlos Koundouriotis in Thessaloniki, October 1916, arriving to establish the Provisional Government of National Defence. Photo by Ariel Varges.

Cosmos Philly is made possible through the support of sponsors and local partners. If you’d like to become a sponsor or promote your business to our community, get in touch.