On August 4, 1936, General Ioannis Metaxas, with the backing of King George II, suspended the Greek parliament and assumed full control of the government. That day marked the beginning of the 4th of August Regime, an authoritarian rule that would last until 1941.

It was a shift that ended democratic politics in Greece for years and left behind a legacy that is still debated today.

Greece in Turmoil

The early 1930s were difficult for Greece. The global economic crisis had taken a heavy toll, especially on workers and farmers. Exports collapsed. Unemployment soared. Strikes and protests became common.

At the same time, Greek politics were paralyzed. The January 1936 elections had produced no clear winner. The Liberal and Populist parties could not form a stable government, while the Communist Party gained 15 seats and unexpectedly became a power broker in parliament.

This fragile situation worried Greece’s monarchy and conservative elite. When a major strike was announced for August 5, Metaxas responded preemptively. On August 4, he declared martial law, halted key sections of the constitution, and dissolved parliament.

A Government Above Parties

Metaxas explained his actions in a speech to the public. He blamed the political parties for instability and claimed the country faced a serious threat from communism. He called for discipline, unity, and obedience to the state.

His new government banned all political parties, including his own. It outlawed strikes, censored the press, and imprisoned or exiled opponents. He took on the title Arkhigos, meaning leader, and described his rule as a new beginning for Greece.

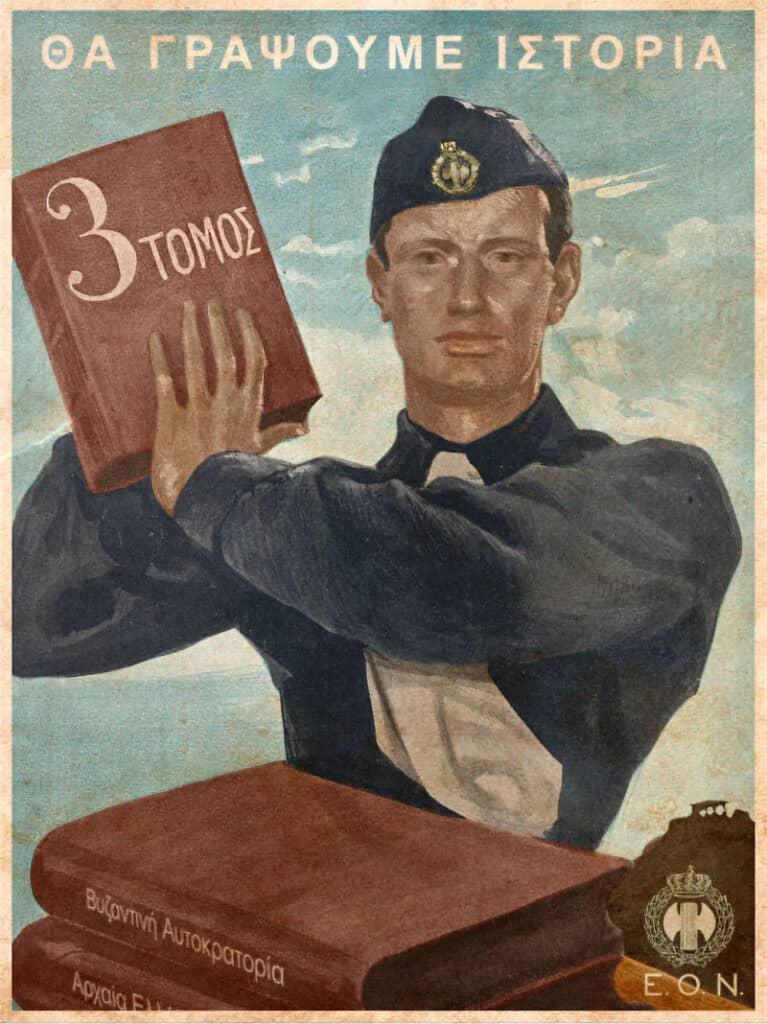

He spoke of building a “Third Hellenic Civilization” that would take inspiration from ancient Sparta, Macedonian strength, and Byzantine tradition. His regime promoted national pride, conservative values, and loyalty to the state.

Youth and Indoctrination

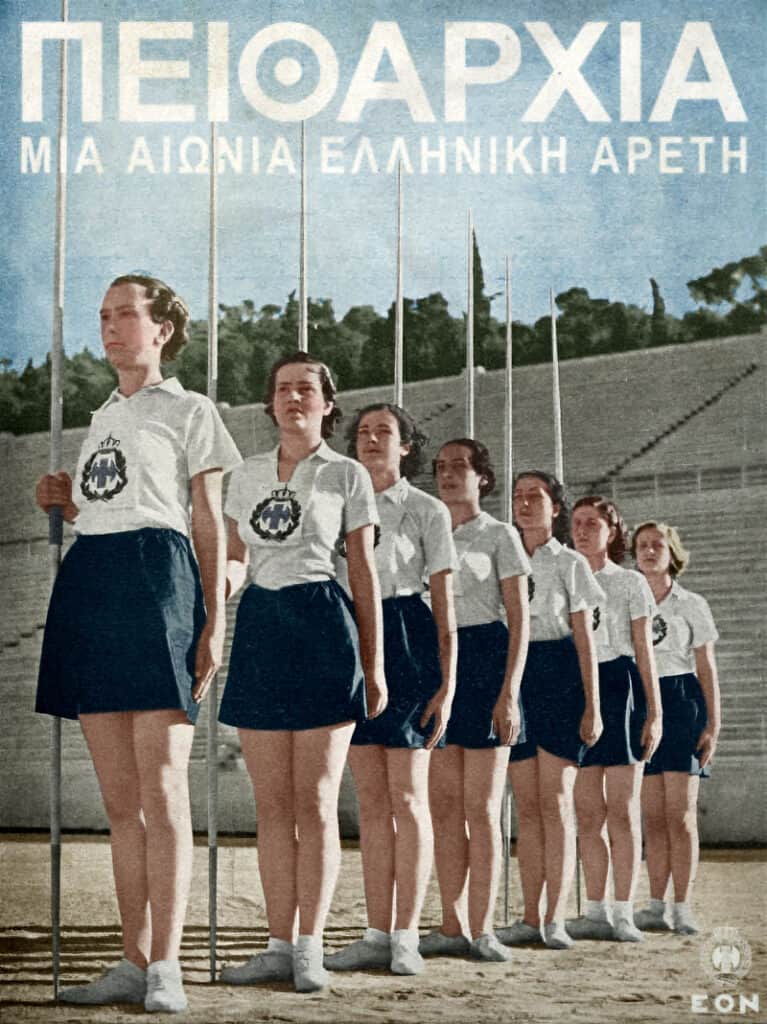

One of the regime’s central tools was the creation of a national youth organization, known as EON (Ethniki Organosis Neolaias). Young boys and girls were enrolled by the hundreds of thousands, dressed in uniforms, and taught to march, salute, and pledge loyalty to the state and the leader.

EON was not just a civic or athletic group. It was a carefully designed program of indoctrination. It replaced independent scouting and emphasized obedience, national purity, and militarized discipline. Textbooks were rewritten. School ceremonies took on ritualistic forms. The image of Metaxas appeared in classrooms, official posters, and newspapers. Greek youth were raised to believe they were heirs to Sparta, led by a father-figure who would restore the nation’s greatness.

Although the organization was not explicitly modeled on the Hitler Youth, it shared many of the same characteristics. It followed a hierarchical structure, promoted paramilitary drills, and relied heavily on symbolism. Girls had their own parallel programs, focused on health, domestic virtues, and patriotic motherhood.

Culture and Spectacle

The 4th of August Regime invested heavily in public displays. Parades, open-air rallies, torchlight processions, and anniversary celebrations became common. The regime’s visual language borrowed from classical antiquity, including columns, laurel wreaths, and Doric patterns, blended with nationalist imagery designed to project strength and unity.

One of its core slogans was εθνική αναγέννηση (ethniki anagennisi), or “national rebirth.” This idea framed the regime as a break from κομματοκρατία (kommatokratia), or “party-ocracy,” which Metaxas blamed for division and decline. National unity, obedience, and order were now presented as the only path forward.

Censorship shaped nearly every part of cultural life. Plays, books, and songs that criticized the state or leaned left were banned. Writers and journalists were arrested or silenced. At the same time, the regime sponsored artistic works that aligned with its vision of Greek identity rooted in history, religion, and discipline.

Posters and pamphlets showed simplified, idealized images of workers, farmers, and soldiers, portrayed as healthy, upright, and loyal. The message was clear: the nation came first, and the individual had value only in service to it. Many of these materials survive today in archives and museum collections.

Authoritarian Rule with Social Reform

While Metaxas ruled with a heavy hand, he also introduced policies that improved working conditions. In 1937, the regime passed labor reforms including the eight-hour workday, five-day workweek, paid holidays, and the foundation of the Social Insurance Institute (IKA). Although implementation was uneven, these measures were a first in Greek labor law.

The regime also invested in infrastructure and public services. Farmers benefited from debt relief and better crop pricing. These policies won some support, especially among rural and working-class Greeks. But they did not lessen the regime’s reliance on censorship, propaganda, and police control.

Social initiatives were closely tied to the regime’s messaging. Government posters and public speeches presented the state as a firm but caring protector. Reforms were not described as rights earned by workers, but as generous acts from a fatherly government. This helped justify authoritarian control while removing the space for labor organizing and democratic debate.

The regime also sought to limit class conflict by positioning itself as a unifying national authority. Metaxas framed labor and capital as two parts of the same national body, both subordinate to the interests of the state. Independent unions were dissolved, and a state-controlled labor front replaced them. Workers gained some material protections, but they lost the power to negotiate or organize freely.

Diaspora Reactions

In the Greek-American press, early reactions to Metaxas were mixed. Greek-language newspapers in cities like New York, Boston, and Chicago followed events closely. Some publications, especially those aligned with Venizelist or republican views, expressed concern about the loss of democratic institutions. Others, particularly in conservative church-affiliated circles, welcomed the emphasis on order and tradition.

In Philadelphia, smaller community papers made occasional mention of the “4th of August government,” especially in the context of its rejection of communism and moral reform. The youth programs and national celebrations in Athens were sometimes framed as signs of renewed pride in the homeland, even if the political reality was more complex.

By the time of the “Ohi Day” moment in 1940, diaspora opinion became more unified. While systematic evidence is limited, surviving press coverage shows that many Greek-American communities rallied around the homeland in the face of Italian aggression, regardless of their earlier political leanings.

War and a Turning Point

In October 1940, Mussolini demanded passage for Italian troops through Greece. Metaxas refused. His reported answer was a simple “Ohi” (No), which led to the Greco-Italian War. Greece fought back successfully, and Metaxas gained new respect as a symbol of national resistance.

He died unexpectedly in January 1941 from a throat infection. Although the regime lost its central figure, the dictatorship continued under Prime Minister Alexandros Koryzis and King George II. It officially collapsed only in April 1941, when German troops entered Athens.

Fascism, Nazism, or Something Else?

Although Metaxas borrowed certain outward elements from fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, such as youth organizations, mass rallies, censorship, and the Roman salute, his regime is not typically classified as fascist in the full ideological sense. It lacked a mass political party, had no racial doctrine, and did not promote expansionist war aims. Metaxas himself rejected alignment with Nazi Germany and maintained Greece’s traditional ties with Britain.

At the same time, the regime did express cultural chauvinism and promoted a narrow vision of Greek identity. Religious minorities, particularly Jews in Thessaloniki, faced pressure to conform to the regime’s national-Christian identity. The state barred non-Christians from youth groups like EON and tolerated antisemitic rhetoric in nationalist circles, but it did not enact racial laws. In some cases, it even repealed earlier antisemitic measures and curbed violent groups like the EEE militia. Still, the social message was clear: Greekness meant Christian orthodoxy.

Historians often place the 4th of August regime closer to other conservative authoritarian governments of the time, like Franco’s Spain or Salazar’s Portugal. It was anti-communist, nationalist, and paternalistic. Its central goal was stability, not revolution. The regime’s ideology, often called Metaxism, focused more on hierarchy, obedience, and cultural revival than on the radical transformation seen in full fascist or Nazi systems.

Looking Back

Today, August 4 stands as a reminder of how quickly a democracy can be replaced by a centralized regime. It shows how ideology, fear, and national crisis can reshape a country’s direction. It also raises larger questions. What makes a regime legitimate? Can authoritarianism ever be justified by reform? And how should we remember leaders who ruled with both a strong hand and a public welfare agenda?

Metaxas’s rise did not happen in isolation. It followed a broader pattern seen across Europe in the early twentieth century. In Italy, Benito Mussolini came to power in 1922 with support from the monarchy and industrial elite, after years of political gridlock and labor unrest. In Germany, Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor in 1933, then used a national emergency to dismantle democracy from within. In both cases, authoritarian leaders claimed they were rescuing their nations from chaos.

Metaxas followed a similar path. He was invited to lead during a moment of crisis, used legal mechanisms to consolidate power, and built a system that combined repression with social reform. But unlike the fascist regimes of Italy and Germany, his rule was more conservative than ideological. He had no mass party behind him and no vision of global expansion.

The model reappeared again in Greece in 1967, when military officers staged a coup just before national elections. That dictatorship also claimed to protect the country from communism, suspended civil rights, and ruled by fear. Once again, democratic institutions were set aside in the name of national unity.

These comparisons help place the 4th of August Regime in context. The forces that shaped it, including economic instability, political paralysis, and fear of the left, were not unique to Greece. They were part of a larger European story. What happened on August 4, 1936 was one chapter in that history. Its lessons still resonate today.

After Metaxas: War, Occupation, and Civil War

When Metaxas died in January 1941, his regime lost its central figure, but the dictatorship remained in place under Alexandros Koryzis and the King. By April, Nazi Germany had invaded Greece. The country, weakened by earlier battles with Italy, fell within weeks.

From 1941 to 1944, Greece was under Axis occupation. The years that followed were marked by hunger, repression, and organized resistance. Leftist and nationalist groups both fought the occupiers, but they also began fighting each other. As the war came to an end, the divisions that had festered during the dictatorship and deepened during the occupation exploded into civil war.

Between 1946 and 1949, Greece was torn apart by an internal conflict between the government, backed by Britain and later the United States, and the communist-led Democratic Army of Greece. Tens of thousands died. Villages were burned. Families were split by politics, exile, and fear.

This civil war would shape Greek politics, memory, and migration for decades to come. In many ways, the seeds of that conflict were already present during the Metaxas years, when political freedoms were taken away, and when silence became a habit for survival.

The featured image in this article is AI-generated. It depicts a fictional 1930s street scene in Athens with a historical 4th of August Regime poster placed in context. While inspired by real events and visuals, the image itself is a digital reconstruction created for illustrative purposes.