Geography, so goes the saying, is destiny. Belgrade is a city founded by natural geography and political geography. A hilly salient at the confluence of two major rivers, the Danube and the Sava, Belgrade always figured prominently in commerce, conquest, and conflict. Few cities I have visited conjure up instantly conflicting feelings of center and periphery as this hilly, charming, and haphazard city.

Geography accentuates the dual (and dueling) sensations of proximity and distance in Belgrade. The city is so close to Central Europe geographically, yet so far away culturally. Despite the distance from Salonika, Belgrade more accurately resembles the Aegean metropolis in terms of feel and culture than it does Central European towns just across the Danube. Belgrade is a vibrant European city, close in proximity to the heart of Europe, yet its mindset, stoicism, and culture make the city seem far away from other Danubian towns further up the river.

Borders and shading always fascinate me, and Danubian, Balkan Belgrade, is both a frontier and a center. These kinds of places often foster creativity among the inhabitants, and a built-in cosmopolitanism. Such places also foster a certain insecurity. Thus, Belgraders (Beogradjani) will emphasize, in word, deed, and architecture, their modernity, their Western-ness, and at the same time, their distinctive, Byzantine identity. Their location points them toward Central Europe, but their hearts yearn for Byzantium. Two Belgrade landmarks provide an illustration.

The first landmark is rather new, St. Sava’s Cathedral, the largest church in the Balkans and “St. Sophian” in its splendor. To drive into old Belgrade, across the Sava River bridges, and to see the cathedral on Belgrade’s highest hill, golden red at twilight as the sun illuminates its white marble exterior and its expansive dome, is to recall the words of a then-pagan Russian envoy to Constantinople, upon entering Agia Sophia over 1000 years ago, “we did not know whether we were in Heaven or on the Earth.” A similar feeling emerges from St. Sava. Further, it is a deliberate stamp of Byzantium on a city at the frontier of the Balkans. Years after I first saw St. Sava in Belgrade, I had a similar feeling when crossing the Golden Horn in Constantinople from Galata, and viewed Agia Sophia. The similarity is far from accidental.

The other monument is Kalemegdan Fortress, Belgrade’s acropolis, for lack of a better word. Here, where two rivers meet on a hilly outcrop, Belgrade’s prehistoric inhabitants built their first trading and defensive settlements. Rome’s architectural stamp is in evidence, as is Byzantium, Medieval Hungary, and of course the Ottomans. In World War One, the Austrian frontier was just across the river, and the centuries-old fortress continued to serve its purpose as the guardian of Belgrade, as it did in subsequent aerial bombings in 1941—and 1999. Like hermit crabs, each master of Belgrade assimilated the structure of the previous owner, and a very subtle monument of the transfer to its current and hopefully final custodians is celebrated in a marble plaque on the manicured park lawn of Kalemegdan, celebrating the day in the 1860s when the Turks turned over the keys of the fortress to the Serbian principality.

Sites chosen for strategic vantage in war and commerce are often romantic in peace, and Kalemegdan in late summer, with the hint of autumn breezes, gardens, and the ubiquitous cafes overlooking the combination of two massive rivers, stirs the strings of the heart as well as the intellect. In Serbia, I believe that the romance is deeper because historical and cultural monuments are not subjected to the conveyor belt of mass tourism. A traveler in Serbia has the opportunity for greater intimacy with the surroundings than in more visited destinations.

Below the steep heights of Kalemegdan, moreover, just a few steps from the confluence of the Danube and Sava Rivers, there is a very important place in Balkan history. It is the site of Rigas Pheraios’ imprisonment and ultimately his execution by strangulation at Turkish hands. The Nebojsina Kule (Nebojsa Tower) has been restored by the Greek government and now houses a museum celebrating his life and goals for a Balkan Federation. In old Belgrade, just outside the Kalemegdan complex, the Serbs have erected a statue in his honor as a patriot for both the grcki i srpski narod (the Greek and Serbian people). Small wonder, therefore, that one of the key Greek organizations in Belgrade is named for Rigas Feraios.

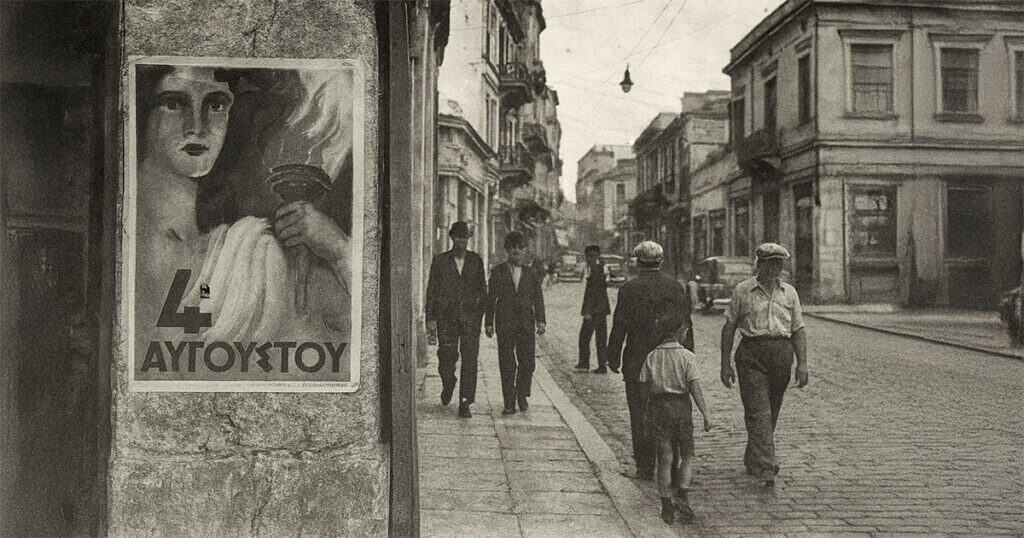

Greek is often heard on the streets of Belgrade, whether from Greek students in one of the various faculties of Belgrade’s university system, Greek investors and industrialists, tourists, or others, like me, Greeks married to Serbs. At the time of Rigas’ execution, moreover, Greek was heard as regularly as Serbian on the cobbled streets of the old city, and many old Belgrade families will proudly cite their origins in Macedonia, Epirus, or Thessaly.

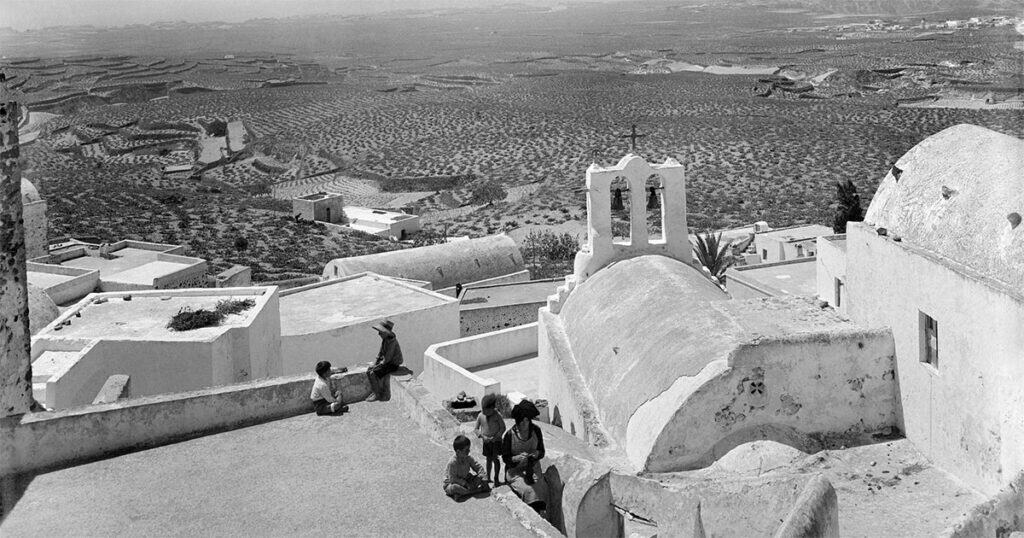

Given these ties and the profound depth of Serbs’ Byzantine Orthodox culture, it is no surprise that Belgrade feels “like home” to Greeks. After visiting Salonika for the first time, my wife immediately compared the Macedonian port to Belgrade, and truly there exists a real similarity between the two Orthodox cities. They do, however, share a common culture and religion, and this Byzantine identity, incorporating both Slav and Hellenic elements, makes the denizens of each city feel at home in the other. The similarities of the two cities are a good example of the victory of culture over geography.

When we visited Istanbul, the topographical and architectural scene even more closely resembles Belgrade, with the narrow channels of the Bosporus and the Golden Horn harbor substituting for Belgrade’s Danube and Sava river confluences. Hills, winding streets, forts, cafes, churches, mosques, all point to membership in a commonwealth that spanned well over one thousand years, under its Byzantine, Ottoman, and Serbian auspices. Belgrade is the northern gate to this incredibly profound Byzantine-Ottoman zone.

Belgrade does, however, benefit from close proximity to Central Europe, which technically begins just over the river in Vojvodina province, where my wife is from. Here over a dozen nationalities live, and in spite of the province’s Serbian Orthodox majority, and its separation by only a river from Belgrade, immediately the atmosphere changes from Byzantine to Habsburg. The towns and architecture conform to the norms of Vienna and Budapest. On the edge of this Habsburg cultural zone, Belgrade readily absorbed much of its culture, even as Serbians in formerly Austrian Vojvodina planted their Orthodox culture firmly in Central Europe.

Belgrade is, therefore, a mixture of influences, and this dueling duality—in edifice and culture—makes Belgrade an interesting place to discover. Walking Belgrade’s streets and pedestrian zones, rarely level but subject to the undulation of the underlying hills, slightly chaotic in structure, its cafés are full. It is a city where the cuisine edges toward Austria and the cafés alternate between Balkan and smoky, to global trendy, to Viennese gemütlich.

Walk down an alley just off the bohemian Skadarlija quarter, the street steeply sloping towards the Sava River. There we found a fresco gallery affiliated with the national museum. The attendant did not charge admittance, and we entered a series of vaulted rooms filled with replicas of frescoes from Serbia’s innumerable monasteries and churches, precious relics of Serbian past history and present passion and plight. At plaster a bookish fellow painted, painstakingly replicating frescoes from a Kosovo monastery. The frescoes bore a humanity typical of late Byzantine art, which would stoke the fires of the Renaissance further west. Like so many extensively educated Serbs, there was less in the business world to offer him, and so he turned his talents to something longer lasting. His work will continue to inspire long after earnings figures become old news. So will Belgrade, lasting the test of time.