I traveled to Turkey a couple of times, always in the thrall of Byzantium yet charmed every time by the kindness and brotherly feelings of Turkish friends and strangers. I think it is important to emphasize this before beginning a scathing indictment. My many dear Turkish friends, please understand this is not directed against you, and many of you have been at the forefront of protest on this issue, and on broader issues impacting your country.

Turkey is a necropolis of Byzantine civilization. Byzantine monuments and infrastructure all are over Eastern Thrace and Asia Minor, far denser and richer than the nomadic civilization that usurped it, and either copied its monuments (see the Blue Mosque as a descendent of Constantinople’s Agia Sophia) or simply occupied and usurped sacred space like hermit crabs (see Agia Sophia, either Constantinople, Trebizond, and hundreds of other churches). This pain you carry when in Turkey, notwithstanding what for most Greeks or other Balkan peoples is a usually pleasant and hauntingly familiar experience.

The salient truth, lost on mass tourists but not Balkan people or those schooled in history, is that the Byzantines were there first, and that most of the monuments of history and culture associated with Turkey were not built by Turks, unless we count the Byzantines’ Islamicized descendants who make up a very large portion of today’s Turks (but more on that in just a second . . .). As is typical, Greece has hardly promoted a Brand Byzantium to remind the world that the Turks, to paraphrase President Obama’s gaffe, “didn’t build that!” Greece is usually wrongheaded in its policies, and its cultural policies are no different.

The problem is, however, more and more people, most importantly Turks, are learning that “they didn’t build that.” They are digging up family histories where even recent grandparents did not speak Turkish or, more importantly, were not Muslims. They find out that many of the Greeks expelled in the 1920s may have been close relatives, and therefore, what does that make them? In Germany, Greeks and Turks laboring side by side in factories or lining up in grocery stores to buy the same foods find that they speak the same language, Pontian.

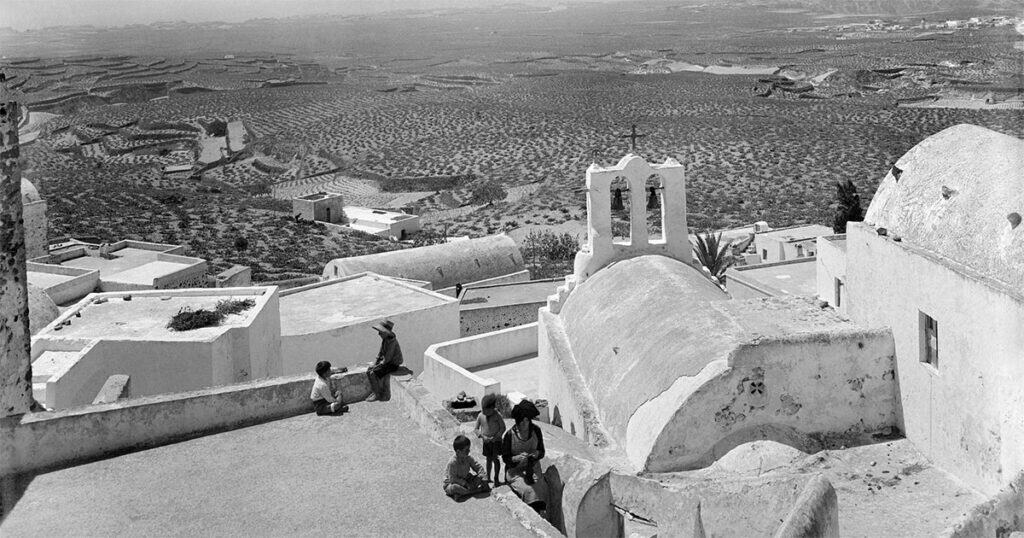

Trebizond is in Pontus. It was the capital of an Empire which developed out of the Crusaders’ attempted dismemberment of the Byzantine Empire in 1204, and it lasted even longer than Constantinople, though its Emperor David lacked the heroism of Constantine Paleologos and handed over the city to Mehmed the Conqueror in 1461, eight years after Constantinople (and one year after Mistra). A huge Pontic Greek population was expelled in the twentieth century, most going to Greece but others to Russia, and officially no Byzantine Orthodox population existed there by 1924.

They did not all get out, and not all of those who remained were killed. In the years of deep-state, regressive Turkey, secrets were best kept as secrets. Pontus for centuries had a tradition of crypto-Christianity. It is ridiculous to think that the tradition ended with the official expulsion of the Greeks in 1923. In the hills above Pontus, around the Monastery of Panagia Soumela, beloved of locals regardless of religion, Pontic Greek remained–and remains–spoken.

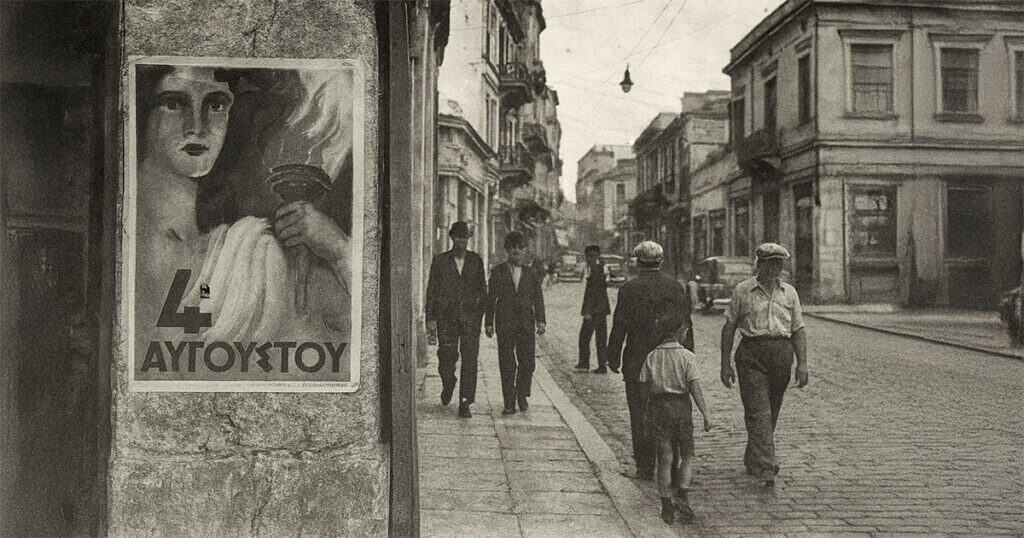

Today’s Turkey is eminently more complicated than the Kemalist Turkey of even a decade or two ago. It has emerged on the world’s stage as an economic, political and cultural great power. It has projected its influence around the neighborhood, using both hard and soft power; Suleiman the Magnificent has become a glamorous soap star with housewives from Belgrade to Baghdad tuning in nightly to watch harem intrigue. At the same time, the tight lid on Turkey’s past is coming off; as a price for opening up to the world, inconvenient truths are coming out. Turkey’s Islamist government is having difficulty coming to terms with this past, just as the past Kemalist governments have, even as a globalized and educated middle class seems to want a European Turkey that is Muslim rather than a Muslim Turkey. Many of these Turks, among them friends of mine, have protested the cultural barbarity of the Turkish authorities.

In the midst of all of this turmoil among Turkish Muslims, a stately Byzantine church in a hauntingly beautiful Black Sea town, which less than a century ago had a Pontic Greek Orthodox majority, could not possibly be left as a museum celebrating its heritage. No, it had to be a mosque, to “ protest too much” that Turkey is Muslim, and to plaster over–figuratively and perhaps literally–the secrets of Turkey’s past (and sometimes present) inhabitants.

Perhaps, as a Greek with a too historical and emotional frame of mind, I am reading too much into this. It would not be the first time. Perhaps not. Erdogan and his cronies may think this step is a sign of strength, of the triumph of Turkish Islam over Orthodox Greeks, or over the more secular or diverse portions of Turkish society. To me, however, it is a sign of weakness and insecurity, which in a place like Turkey frightens me more than strength.