At 3 am on the morning of October 28th, 1940, Emanuele Grazzi, the Italian ambassador to Greece, delivered an ultimatum from Benito Mussolini to Prime Minister Ioannis Metaxas. Il Duce demanded that Metaxas allow the Italian army free passage to enter and occupy strategic sites in Greece unopposed.

By Victoria M. Lord

Faced with this demand, Metaxas delivered an unequivocal response in French, the diplomatic language of the day, “Alors, c’est la guerre.” This brief phrase, “Then, it is war,” was quickly transmuted into the laconic “Oxi,” the Greek for no, by the citizens of Athens.

At 5:30 am, before the ultimatum had even expired, the Italian army poured over the Greek-Albanian border into the mountainous Pindos region of Northern Greece. There they met fierce and unexpected resistance.

Within six months, Ioannis Metaxas would be dead; his successor, Alexandros Koryzis would commit suicide; Mussolini would be humiliated; and the Germans would raise the swastika over the Acropolis.

Despite Greece’s ultimate fall to Axis powers, Metaxas’ response resulted in a fatal diversion and delay for the Axis powers in general and the German army specifically. British military historian Sir John Keegan describes the Battle of Greece as “decisive in determining the future course of the Second World War.”

For decades prior to the invasion, Greco-Italian relations had been difficult and complex: historically, both Italy and Greece could lay claim to some of the same territory. At various times the two nations tussled over the Dodecanese Islands as well as the island of Corfu in the Ionian Sea. However, in 1928, then Prime Minister Venizelos had signed a Friendship Agreement with Italy, normalizing relations.

In 1939, the Italian invasion of Albania threatened this fragile accord. Albania collapsed under the Italian onslaught: Italian troops attacked on April 7th, almost immediately gaining control of all ports. King Zog and his family fled south to Greece that same day, abandoning their people.

On April 12th, the Albanian parliament voted to unite with Italy, deposing Zog, and accepting the Italian King, Victor Emmanuel III, in his stead.

The presence of Italian troops in Albania, just over the border from Northern Greece generated enormous tension between the two countries. Both Britain and France gave Greece a guarantee of “territorial integrity.” Nonetheless, Italian forces committed numerous acts of aggression against Greece, including overflights of Greek territory and attacks against Greek naval vessels.

Metaxas began to prepare for war.

In a great irony, Italy’s actions drove Metaxas, who had cultivated friendly trade relations with Nazi Germany, into the arms of Britain. While Metaxas initially favored Germany, King George II was a confirmed anglophile. Italy’s intervention provided the excuse for the king to push his Prime Minister toward closer relations with Britain.

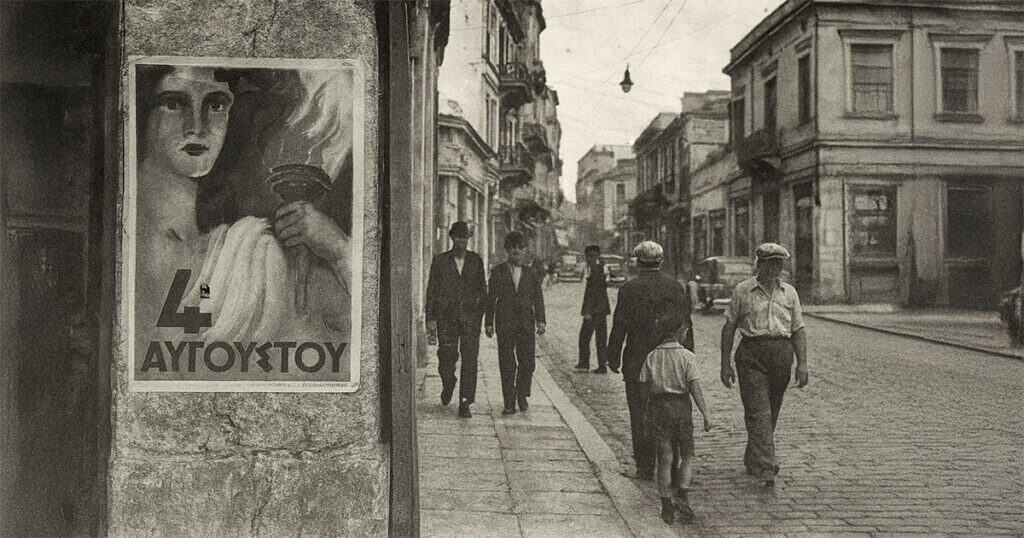

Ioannis Metaxas had begun his career in the Greek army, eventually entering politics as a staunch royalist. By 1936 he held the post of Minister of War. That same year, a deadlocked election led King George II to appoint Metaxas to the position of Prime Minister.

Within four months, Metaxas had declared a State of Emergency and suspended Parliament. For the remainder of his life, he ruled as a dictator. He is a deeply controversial figure in Greek history but his actions on October 28th contributed to the ultimate victory of the allied forces.

Mussolini’s advisors had assured him that the invasion of Greece would take no more than two weeks. The Italian experience in Albania must have made this seem very plausible: like Albania, Greece was a small country with a correspondingly small army.

The difference lay in the territory: Italian forces entered Greece through the steep Pindos Mountains. This was rough, wild terrain made worse by the onset of winter. As Italian troops moved southward towards the city of Ioannina, Greek troops took to the heights, bombarding the Italians from above.

The rough roads and deep snow made it difficult to supply the troops, while bad weather and continuous cloud cover prohibited the Italians from using their superior air power.

Meanwhile, the women of the local villages, accustomed to the territory, carried supplies and munitions on their backs to the Greek troops.

Argiris Balatsos recorded his encounter with several of these women in his diary:

“7 November 1940. …I met women who were carrying ammunition. One was 88 years old. Another one told me that she had locked the kid in the shed, so that she could come to help the army. During the night, I saw an old woman taking care of the two kids, while their mother was baking bread for the army under the candle light.”

The British, who had promised to aid Greece, were hard pressed themselves. By the autumn of 1940, they stood alone against the Germans and had no troops to spare for the defense of Greece.

However, British troops had occupied Crete on October 3rd, 1940, with the full permission of the Greek government. This freed Cretan troops, among the fiercest of Greek soldiers, to fight on the mainland in the Pindos Mountains.

Within three weeks, Greece was completely free of the invading forces and began a counterattack, driving deep into Italian-held Albania.

Mussolini was humiliated and enraged. Hitler was also furious at what he viewed as Mussolini’s blunder.

On January 29th, 1941, Prime Minister Metaxas died suddenly and unexpectedly from an inflammation of the pharynx that led to a toxic infection. Alexandros Koryzis, the Governor of the Bank of Greece, succeeded him in office.

In March of 1941, Mussolini personally supervised a ferocious counterattack designed to drive the Greeks from Southern Albania. Despite his leadership, the attack failed, further humiliating the Italian leader.

By April, the small Greek army had been fighting for six months. Exhausted, they now faced a new threat. Bulgaria had joined the Axis powers, and the German army advanced toward the Greek-Bulgarian border. Here, the Greeks had been well prepared for an invasion: Metaxas had built fortifications all along this border.

Unfortunately, the Germans also poured over the undefended border with Yugoslavia. Initially repulsed at the Metaxas line, the Germans quickly overcame the Greeks.

On April 18th Prime Minister Koryzis chose to shoot himself rather than face the German entry into Athens.

Just nine days later, German motorcycle troops entered Athens, driving straight to the Acropolis. There, they tore down the Greek flag and replaced it with a Swastika.

Despite their ultimate defeat, the Greeks had fought long and hard. For six months they occupied the Italian army, preventing them from advancing. In the end, the Germans were forced to delay the invasion of Russia in order to subdue the Greeks when the Italians failed in their efforts. This delay proved fatal for the Germans, extending their campaign against the USSR into the brutal winter.

Hitler’s Chief of Staff, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel admitted during the Nuremberg Trials:

“…the unbelievably strong resistance of the Greeks delayed by two or more vital months the German attack against Russia; if we did not have this long delay, the outcome of the war would have been different in the Eastern Front and the war in general.”

Churchill paid homage to the Greek resistance by claiming, “…until now we would say that the Greeks fight like heroes. From now on we will say that heroes fight like Greeks.”

Perhaps the Greeks were inspired by their own heroic past to wage a fierce fight against all odds. On October 28th, after rejecting Mussolini’s demands, Metaxas addressed the Greek people, ending with this line from Aeschylus’ play The Persians: “The struggle now is for everything!”

With these few words, he evoked the great Greek victory of Salamis over the invading Persian forces. Once more, the Greeks were called to defend their country fiercely.

Every October 28th, Greeks at home and abroad honor the past by celebrating Oxi Day.

Republished from the Ultimate History Project