I grew up in a family of Greek merchant sailors. My father, from Hydra, served in the Greek Navy and then the merchant marines, as did his father, grandfather, brother, cousins, and most of his friends. His father, my grandfather, lost his life in the Battle of the Atlantic during World War Two, along with thousands of other Greek sailors and almost two-thirds of the Greek merchant fleet.

The German U-Boat Submarines devastated the Allied fleets, even sinking ships within sight of the American coast. To make up for the horrific losses, the American industry began a shipbuilding program on a scale never seen before or since. The key to this program was the Liberty Ship, originally a British design for a simple, mass-produced cargo ship. At a time when ships were built with rivets, the Liberties were to be welded, a sacrilege to many traditional mariners. Indeed, some of the first Liberty Ships cracked at these seams, but the cold hard logic of war production prevailed; if the ships made one or two trips, they were considered as a success.

Possessing an abundance of land, capital, labor (increasingly female and minority), and most of all, American ingenuity, these ships could be produced at huge sites around the Pacific, Atlantic, and Gulf Coasts. While the record production time for a Liberty Ship was five days [!], the average was about one month, and in 1943 the United States produced more ships in one year than in the three decades from 1915 to 1945. At the same time, the British and American navies took the hunt to the U-Boats, and cargo ship losses plummeted. Without the supplies brought in the hulls of these ships, there would have been no victory over Germany or Japan.

As the war ended, the US was a victim of its own success both on the field of battle and in production, with a massive surplus of ships and other equipment. Here too, a very American “enlightened self-interest” took over. The US needed to offload ships, and her Allies, such as Greece and Norway, had suffered horrific shipping losses. The solution was to offer Allied nations these ships at the same cut-rate prices and financing as for American companies. The Greeks were by far the largest purchasers, with over 500 ships.

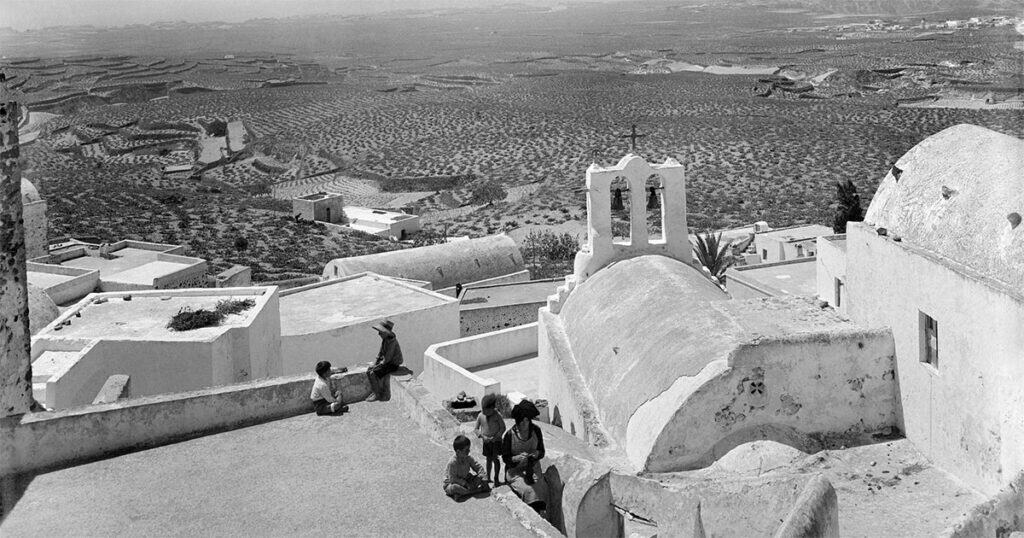

The importance of this transfer cannot be exaggerated. Greece lost over two-thirds of her fleet, a vital source of employment and foreign exchange, and the country was devastated by years of occupation and a looming civil war. Suddenly, a whole new generation of Greek sailors, many, like my late father and uncle, orphans of Greek sailors, took to the sea in a huge fleet of Liberty Ships. These sailors, earning wages far higher than in Greece, and with tax and other perks from a Greek government desperate for foreign exchange, helped to rebuild their families and their country shattered by the wars of the 1940s, and set the stage for Greece’s emergence, however unsteady, as a modern middle-class state. Some, like my father and uncle, jumped from their Liberty Ships to start a new life as proud (Greek) Americans, but others, countless uncles and cousins, remained in Greece.

I spoke to one cousin a few months ago, a retired captain, Velissarios (“Veli”) Theodorou. He started his merchant marine career on a Liberty Ship, in the mid-1960s, and recalls them fondly as solid ships, “particularly when he remembers that they were built for one voyage!” By the 1960s these ships were outclassed by newer ships with more electric and hydraulic systems and faster speeds, but they remained profitable and serviceable ships after over twenty years’ service. He called the Liberty Ships the “yeast” which caused the Greek merchant marine to rise after the disasters of the Battle of the Atlantic. Today, of course, the Greek merchant fleet is the world’s largest, carrying nearly 20 percent of global trade.

My father always spoke in reverent terms about the Liberty Ships. My cousin, of the next generation, echoed his nostalgic affection for these freighters President Franklin Delano Roosevelt called “the ugly ducklings.” These ships helped to win the war, and for Greeks, to secure the piece. Like my late father, these ships conjure a sense of dual pride — for the Americans who built them and who provided them to their Allies, and for the Greeks who sailed them to fortune thereafter.