“You see, I still live like a partisan,” as he showed me his house on the slopes of Mt. Hymettus, in the rapidly suburbanized and gentrified suburb of Peania, outside Athens. The modest house with an attached office and a well-cultivated kitchen garden was indeed Spartan.

These words, from a man who was a contemporary, neighbor and friend of Boris Pasternak, author of Dr. Zhivago, when he lived in Moscow. His best known screenplay, To Nisi tis Afroditis (The Isle of Aphrodite), depicting a Cypriot resistance hero in the rebellion against the British, made him a hero in the Greek world. His fame brought him out of a Russian exile back to Greece, where his communist guerilla background gave way to his patriotic efforts on behalf of the Cypriots. His literary and poetic fame took him throughout America, where he spent months in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles, counting among his friends the great Greek film producer Spyros Skouras.

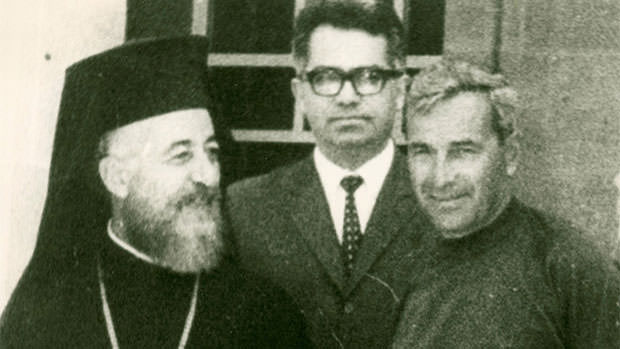

Few people have lived the life of Alexis Parnis, whose literary talent allowed him to transcend the Cold War and ideology and to fight for his beliefs, whether with bullet or pen. Walking into his “office,” we sat down on a simple table with a tumbler of raki a Greek salad, the vegetables straight from his garden, and an octopus meze, an elemental Greek meal. Surrounding us were books and pictures, dust and memories. “A writer’s room,” I thought.

I found out about Parnis, as it happened, by accident. I was researching about the Greek communist community of Bulkes, Yugoslavia, during the Greek Civil War (see my article in the August, 2013 issue of Neo Magazine). My contacts from the Greek Communist Diaspora in Hungary suggested I call Parnis, who had spent several months in Bulkes, for more first hand accounts of this unique community.

After several telephone conversations, wherein I learned that Parnis was the same generation as my late father, and grew up on the same streets of Piraeus, it was clear we had to meet. Parnis’ story went far beyond Bulkes, to the Soviet Union, to Greece, to New York, to California.

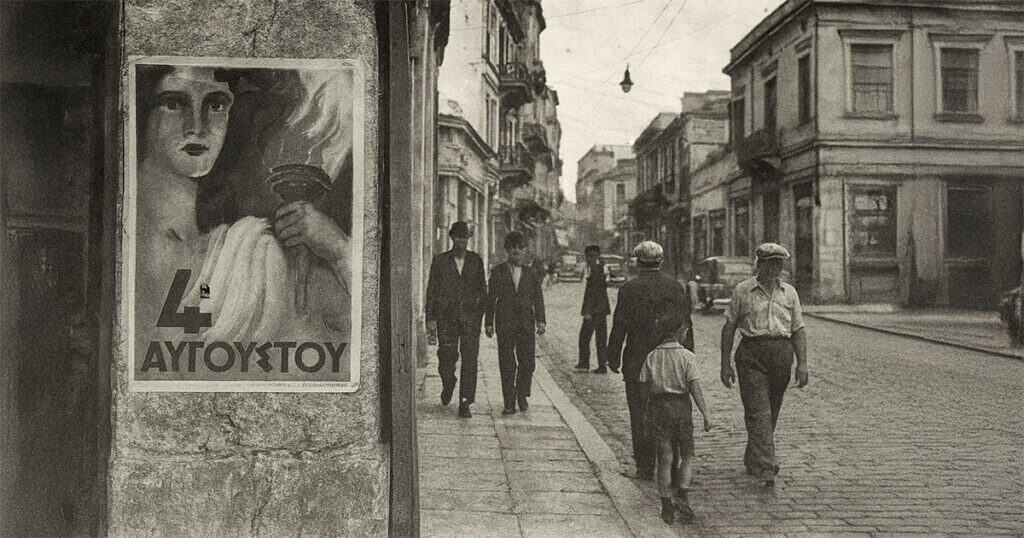

Alexis Parnis was born Sotiris Leonidakis in 1924 in Piraeus, Greece, of a Cretan father and a Maniot mother. Such a combination would no doubt produce a strong, proud, character, and Parnis’ resistance to the German occupier began by his family sheltering a Jewish family, and his efforts are remembered at the Yad Vashem Memorial in Israel. His bravery brought him to the attention of the Communist-led resistance group EAM. “I took up a gun to fight the occupiers of my country,” he said laconically.

Like many resistance fighters, he took a nom de guerre, Kapitan Alexis, and fought the retreating Germans and then the British during the December 1944 Civil War, during which he was wounded severely by a British grenade near Omonia Square. The wounded Parnis was transferred via a torturous route through Roumeli, Epirus, to an ELAS camp in Albania. In convalescence he began writing, found that he had a talent for it, and never stopped.

After the Varkiza Agreement in 1945, several thousand Greek Communists and their dependants were assembled in Bulkes, Yugoslavia (today the village of Maglic in Serbia’s Vojvodina Province). Parnis’ talent for theatre and writing kept him very busy, as the community built a huge theatre which also served for indoctrination and propaganda. “It was during the time in Bulkes that I really learned to write,” Parnis offered. “I would walk around the village, in the midst of the huge trees and the flat land of Vojvodina. On Monday I would develop the idea, Tuesday and Wednesday I would write the play, and Thursday, maybe Friday we would practice, and Saturday and Sunday we would act out the play.”

Parnis was not content to stay at Bulkes, which in addition to functioning as an autonomous “Mini-Greece,” was the rear camp of the Greek Communist guerilla forces fighting in Greece. He fought at the front, and edited the guerillas’ newspaper. At other times, he visited other communist countries as part of a roving embassy. He met several major figures of the era, and eventually ended up in the Soviet Union with the Greek Communist exile Diaspora.

Most of the Greek communist exile leadership ended up in Tashkent, in Soviet Central Asia, but they realized that Parnis was a great literary talent and sent him to Maxim Gorky Literature Institute in Moscow. “I became an overnight success,” Parnis said, in a matter of fact manner, “after I wrote the customary poem praising Stalin.” My face must have betrayed my disbelief, for his sharp near-nongenerian eyes caught my expression. “I know that you find it hard to believe, but at the time, we really believed that we could create a better world. Yes, there were horrible crimes, but the theory was good.” He thought for a minute. “My daughter in school, she was taught that all people are brethren. Tell me,” his rich voice rising ever so slightly for effect, “did the Nazis teach such things in school–I think not!” After hearing the poem, which in reality is the story a female Greek communist prisoner’s child living with her mother and dozens of other women in a cell, knowing neither sun, sea, sky, or mountains, only death on which to draw a comparison, my eyes were hardly dry. Parnis’ emotional and highly human poetry–also present in his prose and screenplays–took the Soviet Union by storm.

Quickly enough he was living in Peredelkino, an artists’ and intellectuals’ enclave near Moscow, and his daughter became a sleigh riding companion of Pasternak. In the Soviet Union, he remained prolific, but always his thoughts were for his homeland. He wrote poetry in praise of Beloyiannis, the Greek Communist leader executed in 1952, for which he won the first prize at the Fifth World Youth Festival in Warsaw in 1955. He offered that his Cretan background and their almost genetic capabilities with mantinades no doubt gave him an advantage.

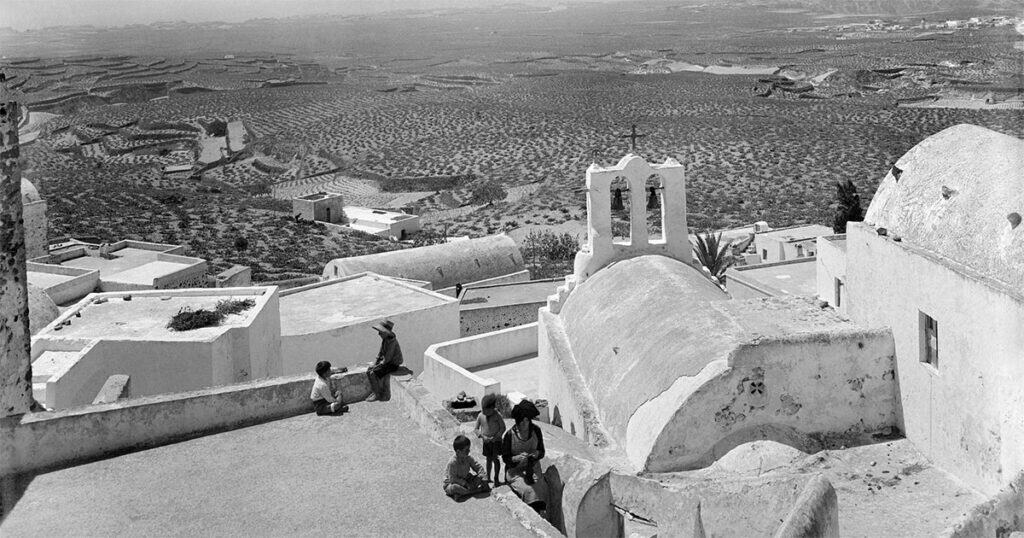

It was To Nisi tis Aphroditis, however, that brought him literary immortality. His depiction of a brave Cypriot freedom fighter and his even braver, selfless mother brought down the house in cinemas all over. This work set the stage for his return to Greece in 1962, despite the Cold War. He was, and is, above politics. In fact, when Parnis returned with his wife and three children in Greece, he may have lacked the money and worldly goods he had to leave behind in the Soviet Union, but he was sent off and received by ministers. “Our great poet Odysseas Elytis himself brought the invitation to Moscow,“ he says, allowing himself a moment to bask in the memory.

Parnis’ work received praise far and wide, and the interest of the Greek American community, not least Spyros Skouras, the legendary Hollywood mogul. Having been feted at the top of the Soviet Union, he then traveled for months in the United States, particularly cities such as New York and Chicago, with large Greek communities, but also Los Angeles. “I wrote one of my books, Leforos Pasternak, while living in the Greek Consulate in Chicago!” Reflecting on the US, he said, “I loved America, the immense diversity there.”

Then, in one of the few times in our hours-long conversation, he brought up politics directly, “Speaking of revolutions, the American Revolution was the greatest. These revolutionaries, unlike others, did not massacre the past to create the present.”

As an American I could not help smiling, but as a Greek, I wanted to hear about the Greek present. “What will become of Greece now?” I asked. He thought for a moment, and said, “Greece will survive. She is eternal.” When I expressed my own severe disappointment after living in Greece, he said, “Do not be disappointed by her, do criticize her though.” Reflecting on himself, he said, “The crisis has not affected me personally, because I never bought into the system here. I have my small pension, and I have money left over, I never took a Resistance Pension.”

“Greece by her resistance saved Moscow. But even more than that, Greece is a light to the world, we are anthropocentric. As technology rises, man falls. Greece is an example. A Greek can go from a lamogia (crony) to a hero in short order.” He did offer though, after those stirring words, his own examples of Greece’s problems. “For EUR 15, there are people I know who will sell their filotimo, and ruin fifty years of friendship.”

I once read a phrase by Patrick Leigh Fermor, the celebrated Greek-based British writer and contemporary of Parnis, commenting on the resilience of those who have Propolemika Kokkala, (Prewar Bones). Parnis has such a constitution. We may argue about the correctness of his cause, but he was not corrupted, not like so many former communists I met in Greece and in Eastern Europe who became rapacious capitalists. In a world (and a Greece) where much is sold for a meal, Parnis remained elemental and fundamental, belonging, really, to no ideology, but to humanity first and to Greece a very close second. As I left he commented about the current Cyprus plight, “The people of Cyprus are again suffering. I must do something to help.”