5/23/2016 — Today, it’s raining here in Chicago, and cold in mid-May. Back in January of 2013, it was just such a cold, rainy day… but elsewhere. At the time, my family still lived in my wife’s hometown of Sombor, Serbia, in the northwestern corner of the country. And as was often the case when the weather was foul, I had repaired to my signature watering hole, the Café des Artes, for a coffee. I was always sure to find good company there, Sombor artists and intellectuals. On this particular day, I ran into Bincho: mid-70s, erudite, ironic, with a ubiquitous cigarette in hand, his glasses and goatee marking him as a proper denizen of any Balkan or Central European café. I sat at his table, ready for banter.

Bincho is Slav-Macedonian, born in Greece just before the outbreak of the Greek Civil War between the Communists and government forces. I looked forward to our talk, in Serbian, English, and Greek. Though we were on opposite camps regarding the Macedonian Issue, at least officially, we’d never exchanged a cross word. Bincho had lost his father to the violence of the Civil War (1944-1945, 1947-1949), yet I detected not an ounce of rancor in him.

On this particular day, our conversation lasted about a cigarette’s length. He mentioned, in passing, a town called Bulkes, a “virtual mini-Greece in Yugoslavia.” I furrowed my brow. “Yes, I read something about Bulkes somewhere; one line in a book about the Greek Civil War,” I said, “Some sort of indoctrination camp for Greek Communists.”

“It was more than that, much more,” Bincho said, pulling on the last of his cigarette. “They had their own ‘civil war’, a Bartolomeski Noc, or St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre.” I looked blank. “A terrible slaughter, here in the middle of Yugoslavia, and in the midst of the Greek Civil War.” Standing up, he added, “By the way, Bulkes is about an hour’s drive from here.”

With that, Bincho stubbed out his smoke and took his leave. “Wait!” I wanted to say. “You don’t just leave someone with my inquisitive nature with such a riddle and then take off!” But, he was gone. Well, I was not about to leave it. I downed my coffee, and headed home.

“Home,” in Sombor was a 19th-century Austro-Hungarian townhouse we’d bought in 2007, and renovated when we arrived from London in 2010. A large front room houses a huge library, full of books I’d brought from the US, Greece, and London, and I began perusing them. Close at hand was my writer’s desk, a mess of papers, and my laptop. I immediately began an online search, in English, Greek, and Serbian.

I also started button-holing people in person. My wife, who grew up in Sombor, had never heard of Bulkes. My in-laws had, vaguely, though specifics were lacking. In those years after World War Two there’d been much movement, out and in, in the region: Germans were expelled from villages in Yugoslavia and elsewhere in Eastern Europe as the war ended, and colonists from poorer parts of Yugoslavia and elsewhere took their place.

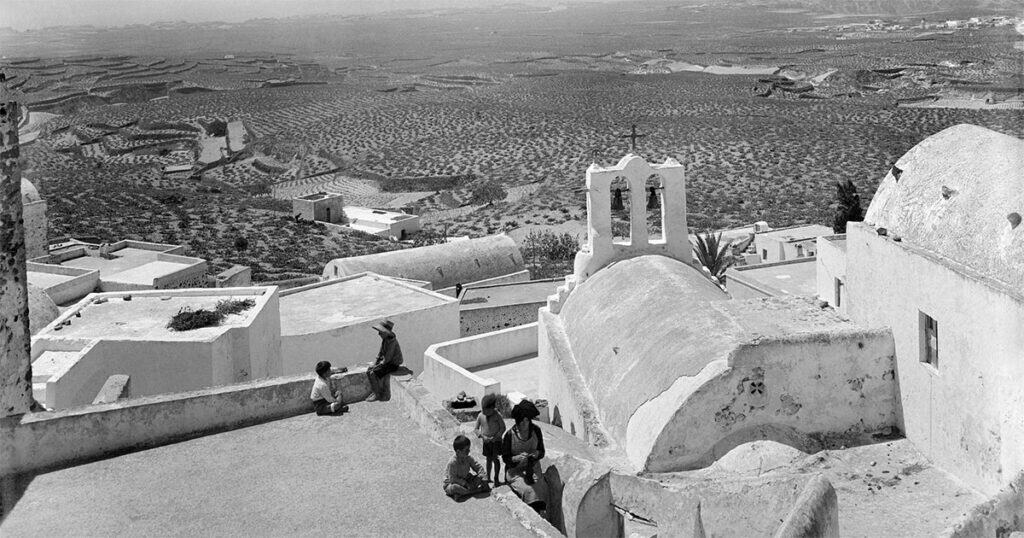

My initial research yielded the following information. Bulkes (now known as Maglić) is a village in Serbia, in the northern province of Vojvodina, where we lived. Vojvodina is different from the rest of Serbia in that it comprises mostly flat, very rich agricultural land, and over two dozen nationalities live in its cities, towns, and villages. Bulkes, like many towns in pre-World War Two Vojvodina, had a German majority, descendants of colonists who had occupied the area since the early 1700s, after Austrian forces expelled the Turk south of the Danube River, in the aftermath of the Turks’ defeat at Vienna in 1683. As World War Two drew to a close, the Germans were cleansed from Bulkes, and it ended the war empty of inhabitants save for a few stray dogs.

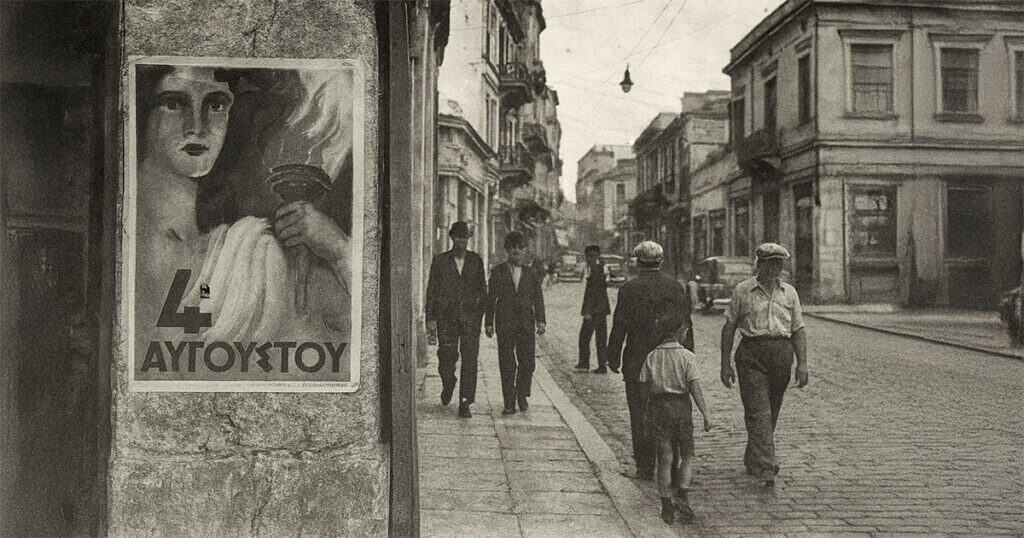

At the same time, farther south, in Greece, the evacuation of the German army of occupation did not signal the end of hostilities in the region, as Communist partisans battled the Greek government and British forces, and right-wing militias, in December 1944. In early 1945, the full weight of the British war machine ended the fighting and a ceasefire agreement was penned in the Athenian coastal suburb of Varkiza.

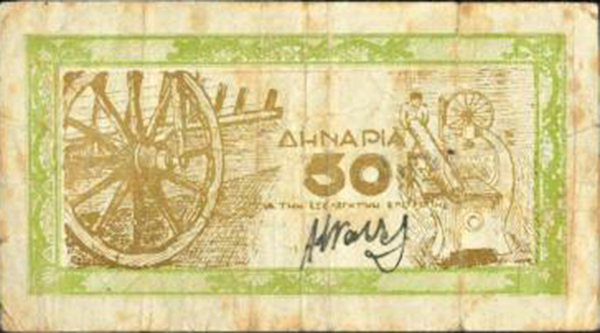

Neither the Greek Government nor the partisans kept their sides of the bargain, however, and low-intensity conflict continued, resurfacing as a full-scale civil war in 1947. Moreover, as all of the countries directly to Greece’s north had fallen under Communist control, many partisans slipped over the border. They were massed in Bulkes which, for the next four years, served as a “mini-Greece” within Yugoslavia, with its own laws, media, the Greek language, and a private currency—Bulkes Dinars, valid only within the village. Residents took over the former German residents’ sturdy houses and farms, founded schools, newspapers, military depots and, most importantly, built a huge theater.

Bulkes enjoyed autonomous status in Yugoslavia and functioned as a distant base camp for the fighting several hundred kilometers south, in Greece, where the Civil War erupted again in 1947. As my friend Bincho had said, Bulkes contained factions and, over the course of three days in mid-1948, the camp was ripped apart by its own mini-civil war, stoked by local tensions as well as by the shifting tectonic plates of geopolitics.

When the Yugoslav army and police stepped in to stem the carnage, bodies were everywhere; the wells filled with corpses. In 1949, almost as abruptly as it was founded, the Republic of Bulkes was dissolved. As though it had never existed—and officially in Greek and Yugoslav/Serbian history, it was expunged—Bulkes was gone.

I, however, was not satisfied with all the loose ends I’d turned up.

Searching the internet for further clues, I found that most of the sources I could pinpoint were Serbian, including a blog post by a man named Bojan Djurisic, a photographer and cinematographer from Sombor who had done some work about Bulkes.

I contacted Djurisic via his website, www.bojandjurisic.com, and he put me in touch with Sinisa Bosancic, a young filmmaker born in Maglić, the former Bulkes, in the 1980s. We arranged to meet in Novi Sad, Serbia’s second largest city. Novi Sad lies on a bend of the Danube River, about 100 kilometers from Sombor. I knew it well and was always looking for an excuse to go there.

I found Bosancic in a grimy but hip café located in a stoa off a main street, a joint lined with books, old concert posters, and clouds of unfiltered cigarette smoke. Bosancic, like so many Serbs, could easily pass for a Greek. As he’d been born in Bulkes, I asked if he had any Greek forebears. “No,” he said, he was from the “next generation of colonists.” After the Bulkes Greek community was disbanded by the Yugoslav authorities in 1949 and the Greeks expelled, Bulkes was once again empty, just as in 1945, when the Germans were deported and, in the early 1950s, Serbs from Bosnia, like his grandparents, colonized the town and renamed it Maglić, after a mountain in Bosnia. As we sipped our drinks, Bosancic gave me a rundown of the Bulkes Slucaj, or “Bulkes Case.”

Most of what he told me I’d already uncovered in my own research, but he emphasized the secrecy and denial of the Serbian authorities. For example, Bulkes, like the other six Yugoslav republics, had its own account at the Yugoslav National Bank, but its archives were “unavailable,” they officially deny ever printing Bulkes Dinars (in spite of their existence), and when Bosancic and other researchers found the former Yugoslav Army officer responsible for transporting the Greeks to Bulkes from the Greek frontier, he refused to talk without the “express authority of the President [of Serbia].” He suggested I leverage contacts I might have in Greece or among the Greek Diaspora in Eastern Europe; we promised to stay in touch.

Luckily, I had Greek contacts in Hungary to draw upon for information. Sombor is only 20 kilometers from the Hungarian border, and I traveled to Hungary quite often. In 1990, I’d lived in Hungary for a semester as a university student, I speak the language passably, and knew my way around the country. Hungary has a substantial Greek community, refugees from the Greek Civil War, when several hundred thousand Greeks fled, willingly or otherwise, to Eastern Europe. A whole village was built by these refugees, Beloiannisz (Beloyannis), about 60 kilometers south of Budapest, named after a martyred Greek Communist official. I’d visited the village and knew the mayor, as well as people from the Greek Community Center in Budapest. I kept hearing the name “Alexis Parnis” mentioned as “the man to talk to” about Bulkes. Bosancic had mentioned him as well.

Often, chasing one story a writer finds another, related, but wonderfully different story.

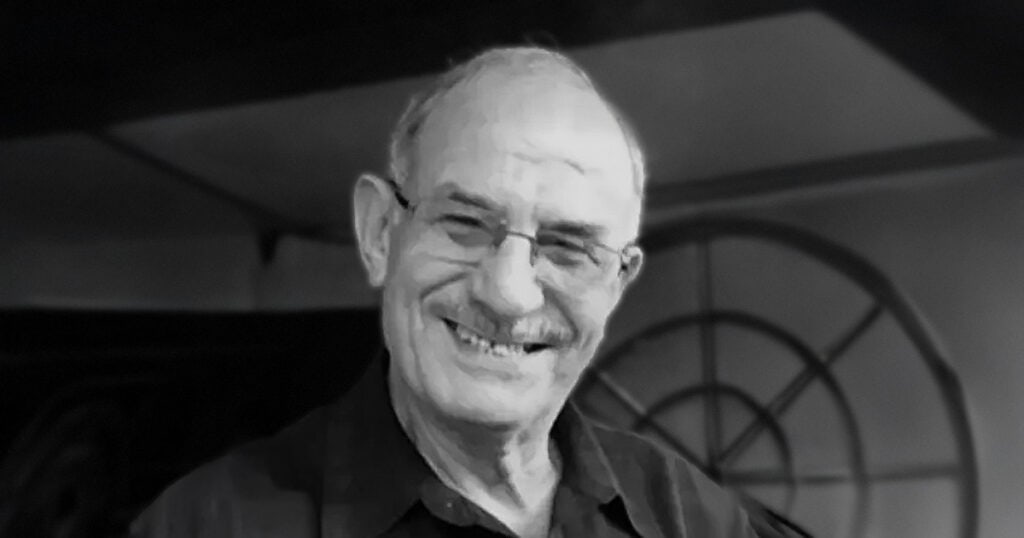

I picked up the phone to call Alexis Parnis at his home in Athens. A warmly gruff old man answered, and I introduced myself. He responded politely but in general terms only, saying that he remembered fondly Vojvodina Province in Serbia, with its “impossibly tall trees,” but it was clear he was not going to give up the story easily. Parnis suggested other sources, and urged me to read his many books, and see his most famous work, To Nisi tis Afroditis (“The Isle of Aphrodite”), about the Cypriots’ struggle for independence, a film that had once made his a household name in the Greek world.

He also asked where I was from in Greece and, upon hearing that my late father had grown up on the same streets, at the same time, in the same neighborhood as he in Piraeus, Athens’ port, he warmed considerably. “Next time you’re in Greece, come see me,” he said.

I visited Greece from Serbia in March 2013, a project-packed trip that would include a lecture on Rhodes, an interview with the Serbian ambassador to Greece, and a talk with Parnis. I arrived at the filmmaker’s home in Glika Nera, an Athenian suburb on the slopes of Mt. Hymettus. His study was book-lined, decorated with pictures and mementos, yet the house, with its working kitchen garden, was Spartan. “You see, I still live like a partisan,” he told me, his near-nonagenarian eyes bright and smiling. In his study, a simple wooden table was set with a tumbler of tsipouro (the Greek equivalent of Serbia’s rakija), a Greek salad, and grilled octopus in olive oil: a simple, elemental Greek meal, the fare I love most.

His story was not atypical of young, intelligent Greeks caught up in the maelstrom of war, occupation, and activism in the mid-20th century. His first act of resistance was to help his family shelter Jewish neighbors, after which he played a more active role in a Communist-led resistance group. He put it laconically, “I took up a gun to fight the occupiers of my country.” In addition to the Germans, he fought the British in the Battle of Athens, in December 1944, received a serious wound, and was evacuated, via tortuous mountain footpaths, to Albania and, from there, to the “Bulkes Republic.”

At last, I’d actually found a “citizen” of my phantom “republic.”

It was there, in convalescence, that he “really learned how to write.” The Bulkes authorities had built a large theater, where propaganda and educational skits were performed every Sunday, perhaps as a substitute for the church previously so important in Greek life. “On Monday,” said Parnis, “I would develop the idea, Tuesday and Wednesday I would write the play, Thursday and Friday we would practice, and Saturday and Sunday we would act out the play.” Bulkes he described vaguely and positively, based on his own experiences there, saying that there was a real community with families, not merely the gulag of “Kafkaesque paranoia” described by Nicholas Gage, a Greek-American writer and journalist, in his seminal work Eleni.

Parnis did say that individual commanders in Bulkes were often brutal and that this played a role in the subsequent fratricidal conflict in the town. While the republic was autonomous from the rest of Yugoslavia, the inhabitants of Bulkes did interact with the Yugoslavs around them. Said Parnis, with a smile, “Even romantic liaisons occurred between residents of our village and neighboring villages.”

Parnis went on to write—and fight—editing the Greek Communist guerillas’ newspaper in the mountains of Greek Macedonia and Epirus. After the defeat of the Communist insurrection in Greece in 1949, he lived in exile in the Soviet Union, writing constantly about his absent homeland. His talent earned him entry to the famous Soviet writers’ village of Peredelkino, where his daughter rode on sleighs with Boris Pasternak, author of Doctor Zhivago.

Parnis’s work straddled genres, and his fans crossed ideologies, particularly as regards his most famous work, about a Cypriot resistance fighter, To Nisi tis Afroditis. The film made the Communist intellectual a national hero in Greece. He returned in the 1960s, and then was feted by members of the Greek Diaspora in the US, including the most famous Greek in show business, legendary Twentieth Century Fox Chairman, Spyros Skouras. One book, Leoforos Pasternak (“Pasternak Avenue”) he wrote while living as a guest in the Greek consulate in Chicago.

The subject of Bulkes yielded, over several hours, to his own fascinating life story: Parnis is a man loyal to his principles but one whose principles are hardly defined by one stark ideology. Few individuals in an era of hard ideological frontiers crossed them so easily, without fatal compromise or consequences. As Parnis walked me to the door, he showed me his kitchen garden, whence came much of our meal.

“I never took the pension I was entitled to as a resistance fighter,” he said, unlike so many who rode their war careers to wealth and political fame. He still lived like a partisan, but I left one of the richest discussions of my life still not knowing enough to flesh out the mystery of Bulkes. Parnis said the place had started him on his writing career, and that Bulkes had been more than a military base but, rather, a real community, but his responses to my questions had not yielded specifics. His mind was clear, his grasp of details and figures firm, yet he spoke of Bulkes in generalizations.

When I asked about the mini-civil war there and the dissolution of the community, he remarked, “I was at the front in Greece; I did not experience it.” Later, talking to his grandson, he mentioned one particularly brutal community leader, killed in his bed—but, again, details were not forthcoming. Said Parnis, “This particular one killed hundreds of people in Bulkes, for ‘anti-party activities’ (wanting to return to Greece, forming relations with local Yugoslavs), and sent others back to Greece for arrest.” (Nicholas Gage also documents similar atrocities in Eleni.)

Bulkes’ dark side was less obvious to Parnis as a young artist absorbed in his writing and fighting at the front, but it was real, though the viciousness of the three-day civil war had, perhaps, more to do with local grudges and grievances than with the Tito-Stalin split. Bulkes may have been more than a gulag, but it was not a pleasant place to live; warlords of different factions wreaked havoc on the inhabitants, as in all civil struggles. In fact, nothing about it was “civil,” and this may be why those who survived Bulkes are so quiet even today, including officials of the Greek and Serbian governments.

Parnis and I had forged a real bond, though; we exchanged books, and I continue to receive books from him here in America. Before I left Greece, moreover, he put me in touch with his grandson, Georgios Makkas, whom I met in my favorite part of Athens, the streets of Plaka, beneath the looming shadow of the Parthenon.

British-educated, and an accomplished photojournalist whose socially-conscious work has appeared internationally in newspapers and magazines, Makkas suggested that I talk to people in Serbia who had remained there after the “Bulkes Repubic” was dissolved. He mentioned a good friend of his, Orfeas Skutelis, a Greek-Serbian filmmaker from Novi Sad (who now lives in the US). He and his videographer father Antonis, who was born in Bulkes, “might be able to provide more details,” said Makkas.

I was going to the Serbian Embassy in Athens the next day, to interview the ambassador. Given the official silence and/or hostility of Serbian government and archival sources, I did not have the topic of Bulkes in mind for my interview with the ambassador. Ambassador Dragan Zupanjevac, an elegant, sharp fellow, equal parts Belgrade, London, and New York, spoke to me instead about Greek-Serbian cultural, economic, and political relations, which are excellent, and said he looked forward to their continued growth. Inadvertently, however, our conversation did give me a bit of insight as to the official silence about the Bulkes Case in official Serbian and Greek histories.

The Serbian (and former Yugoslavian) Embassy in Athens is an impressive building, bought by the Yugoslav authorities in the 1950s. The ambassador and I spoke in general terms about the bad blood between Greece and Yugoslavia during the Greek Civil War, and Marshal Tito’s move to improve relations, while burying the past. Tito visited Greece in 1954, marking rapprochement between Greece and Yugoslavia (which followed on from earlier strong Greek-Serbian political ties), after Yugoslavia had openly supported both the Communist insurrection against Greece and agitated for annexing part of Greek Macedonia.

After his split with Stalin in 1948, Tito cultivated friendships everywhere, and Greece, whose relations with neighboring Turkey were souring (as well as with Britain over the latter’s refusal to support Cypriot independence and/or union with Greece), also sought to restore a traditional Balkan alliance. In the process, aspects of the “late unpleasantness” were swept under the rug and, clearly, the prior existence of an extra-territorial Greek entity within Yugoslav territory serving as a base camp for the communization and the possible partition of Greece was best met by both sides with an official “No Comment.” And the silence continues.

As I boarded the plane for Belgrade, a short flight from Athens, I began to imagine a context for the Bulkes Case. The entity’s survival depended on the results of the Greek Civil War, which the Communists were losing, and on the larger context of international relations. The Soviets did not support the Communist insurrection in Greece; Britain and the US armed and actively supported the Greek government, while Yugoslavia supported the Communist rebels, all the while trying to stay independent of Stalin’s Empire. The Greek rebellion, and this anachronistic extraterritorial “republic” in the heart of a Yugoslavia in peril from the Soviets, became… inconvenient. As I have noted several times, though it was a functioning community, it also seethed with tensions and terrors—a small powder keg within the greater Balkan powder keg—and the region is a mother of wars.

About a week after returning to Serbia, I was once again on the road from our home in Sombor, heading to Novi Sad. I caught up with Bosancic again, but my primary destination was Antonis Skutelis’s apartment. Serbia is generally pleasant in April but, on that day, the rain and fog had set in, and the Danube, visible from his apartment, looked dreary and dead. Antonis was born in Bulkes, and his Greek Communist parents remained in Yugoslavia after the community dissolved. He remembers little of the period. “People were coming and going from and to the front,” he said. “The witnesses of life there [in Bulkes] are all passing away and, even when they were alive, they did not talk about it.”

Again, I noted, and to a remarkable degree, all witnesses maintained the official silence about the place.

Even regarding the fratricidal mini-war in the community, Antonis could offer little elucidation, though his son Orfeas added, “They [his grandfather and others] did not talk about it; they were ashamed, perhaps.”

Antonis then gave perhaps the best explanation: “In the last war [the Yugoslav wars of dissolution in the 1990s] I traveled everywhere. Nobody—no side—is telling the truth; there are no clean accounts here!” As if the day were not cold and dreary enough, he bemoaned “the insanity of the human condition,” stating authoritatively and sadly, even banally: “The worst species in the animal kingdom is the human.”

Drawing on the general theme of my talk with the Serbian ambassador, and my knowledge of East European history, I surmised that the “Bulkes Civil War” was a factional struggle between highly factional people, the Greeks. It coincided with the Tito-Stalin split, which bitterly divided Greek Communists between supporters of Tito and the Stalinists. Whatever happened, once they stilled the Bulkes Greeks’ guns, it was clear that the community could no longer remain an island outside Tito’s control.

Meanwhile, the Greek Communists in Greece, fighting from mountaintop to mountaintop, decided to support the Soviets. That was the end. Tito closed the border with Greece, and then dealt with Bulkes, slowly but surely. The community was cut off from Greeks at the front in early 1949, and Bulkes’ inhabitants were forbidden to leave the confines of the village. Then, in September 1949, the inhabitants, refugees from Greece, became refugees again, scattered to Hungary, the Czech Republic, Poland, the Soviet Union, and the four winds.

A few days after my trip to Novi Sad, I went to the village of Bulkes, today’s Maglić. The theater is gone. Like the Greeks before them, the Serbs from Bosnia and elsewhere have, in essence, occupied the former residents’ homes, moving in like hermit crabs and changing little about the structures. Nothing remains to suggest that Maglić was a key base in the Greek Civil War or a flashpoint in the Tito-Stalin split.

Like every Serbian town, Maglić has its cafés, Kafane in Serbian, although this term often connotes a rough and ready bar, which was the case here. I settled in a simple place overlooking the town square, where what looked to be bad coffee was being served. I ordered a beer, and asked (foolishly) the spandex-wearing waitress with bright red hair and jet black roots if she knew that, about 70 years ago, hers had been a Greek town. “What? Never heard that,” she said, looking at me as if I were nuts.

This was not Bosancic’s café in Novi Sad, or mine in Sombor, where conversations carried one off on intellectual journeys. I paid my bill and walked across the square, where a decaying, elegant German Protestant church, empty since 1945, was slowly yielding its ghost to wear and tear. Across the street, smaller in size, was a Serbian Orthodox Church, built by the post-German and post-Greek inhabitants, in a Serbo-Byzantine style the Greeks would have recognized immediately.

My search was over. It was mid-April 2013, and we were scheduled to leave Serbia for Chicago in two months. The “Bulkes Case,” as we’d taken to calling it in our house, had to be put to rest. It would be hard to say good-bye to so many friends, family, and so much history in plain sight, and out of sight.

I went to the house of a family friend, a retired Yugoslavian army officer, for one final chat. My friend knew about Bulkes, expressed no surprise at the official silence, and reminded me, “Here, we don’t go looking for where the bodies are buried.” Perhaps my Serbian wasn’t good enough to distill all of the meaning in his comment, but I got the gist.

As I write this now, just over three years later, I appreciate all the more those I met and what I learned on my journey, as opposed to lamenting all the loose ends. I realize now that I was operating from my own cultural and experiential perspectives. I’m a Greek citizen with life experience in both Greece and Serbia, but I am also, and primarily, an American with an Anglo-Saxon’s cultural preference for transparency and closure.

People in Europe, particularly in the shatter zone of the Balkans, are used to the absence of both transparency and “closure.” Not one generation in the region has escaped political, economic, ethnic, or ideological chaos, and most have also known the harsh hand of a repressive state, a state wherein inquiries such as mine are dangerous to your health, or to your livelihood.

In the Balkans, always, one must compartmentalize one’s thoughts; in no matter is there closure. This revelation, which hits home just as I finish this essay, fills me with dread. Where the events of history are neither fully discussed nor remembered, there can be no transparency, no real sunlight. The truth becomes relative, malleable; and people subject to manipulation. The Bulkes Case, and so many others in the region, remain perpetually “open.”