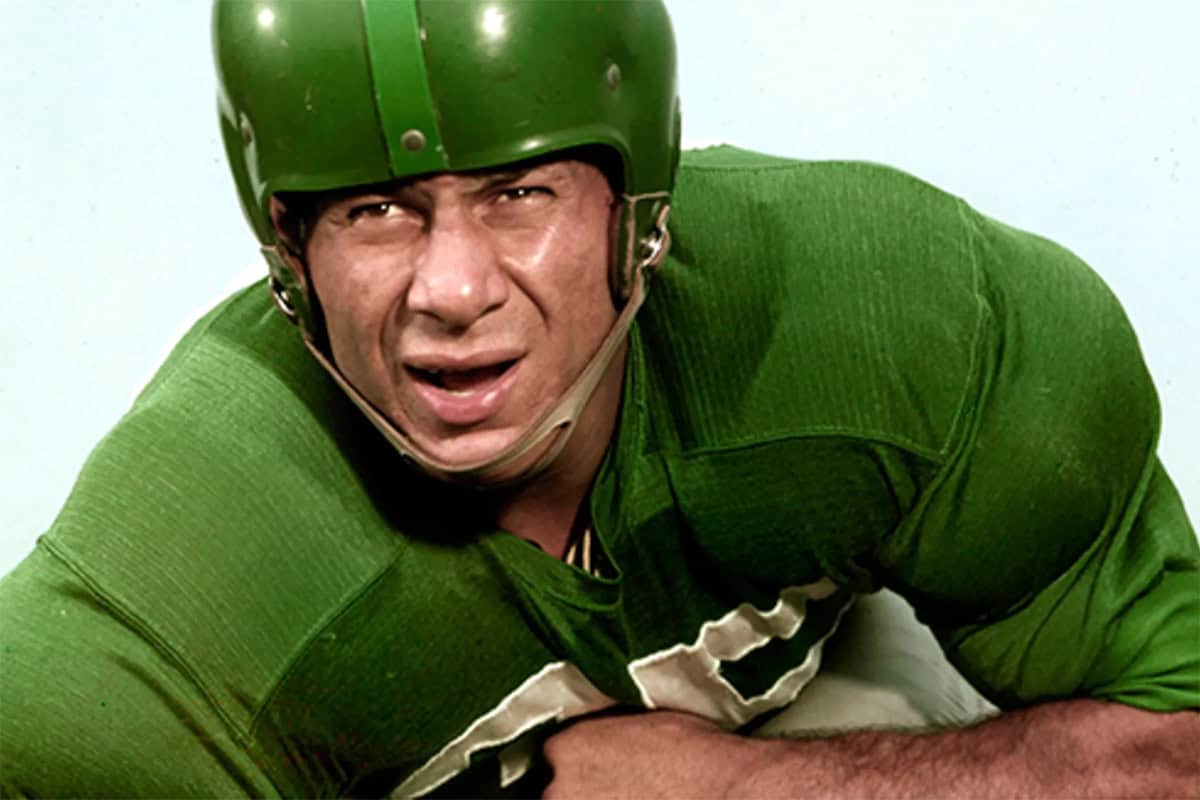

From Orlando to Shibe Park, from South Philly Greektown to a French forest, how Pete Pihos, a Greek American Hall of Famer, his city, and his daughter kept an Eagles legend alive.

Before he became a Hall of Famer in green and white, Pete Pihos was a Greek kid at his parents’ lunch counter in Orlando, the son of immigrants who believed hard work could change everything. The restaurant was more than a business. It was a foothold in America, a place where long hours and steady effort were supposed to lead somewhere better.

That belief was shattered in 1937, when his father, Louis, was murdered during a robbery at the restaurant. Pete was thirteen. The loss wasn’t abstract. It was violent, public, and permanent. For a Greek immigrant family still finding its footing, it had to rewrite everything.

His mother, Mary, moved them north to Chicago, into another Greek enclave, where she rebuilt what she could and where Pete finished high school. He kept playing football. He kept moving forward. Football eventually carried him to Indiana University, where he became an All-American two-way end, a rarity even then. His coach, Bo McMillan, would later call him “the most complete football player” he ever coached. Pihos could block, catch, tackle, and endure. He played the game the way he lived, without shortcuts.

World War II interrupted everything. Pihos served with the 35th Infantry Division under General George Patton. He went ashore in Normandy on D-Day, fought through France, and earned both the Silver Star and Bronze Star. The war was not a chapter he visited and left behind. It was a rupture that reshaped his sense of risk, discipline, and obligation. When he returned to Indiana to finish his degree, he was a different man.

The Eagles had drafted him in 1945, but he didn’t report until 1947. Mary insisted he graduate first. Education mattered. Finishing mattered.

A Greek Name in Midnight Green

When Pihos finally arrived in Philadelphia in February 1947, he was just another rookie to most of the league. In Greek homes across the city, though, his name sounded different. In South Philly rowhouses, in kitchens where radios carried the Eagles’ broadcasts, and in cafés near Eighth and Locust Streets by St. George Greek Orthodox Cathedral, it landed as something close to a miracle. A Greek kid in the NFL. An Eagle.

From his first season, he played as if every snap were a test he refused to fail. As a rookie, he caught 23 passes for 382 yards and seven touchdowns, big numbers for that era. In one game against Washington, he burst through the line, smothered a punt off Sammy Baugh’s foot, scooped it up, and ran it back 26 yards for a score.

His coach, Greasy Neale, put it plainly. “When he gets his hands on a ball, there isn’t much the defense can do,” Neale said. “He just runs over people.”

“He was the most positive person I had ever known,” his daughter Melissa later said. “He always said, ‘Whatever you set your mind to, you can do it.’”

With Pihos in the lineup, the Eagles surged. In each of his first three seasons, they reached the NFL Championship Game. In 1947, they won their first division title and blanked the Steelers 21–0 in a playoff game, thanks to yet another blocked punt by Pihos. They lost the title game to the Chicago Cardinals, but something in Philadelphia had shifted. This was no longer a middling franchise.

At the center of that transformation, wearing number 35, was a Greek American end who never stopped moving.

The Eagles’ First “Super Bowls”

The breakthrough came in 1948 and 1949.

In 1948, the Eagles met the Cardinals again, this time in a blizzard at Shibe Park. Snow fell all day. By kickoff, the field was a white sheet. It wasn’t pretty. It was blocking, tackling, and endurance, three yards at a time. Pihos played both ways, catching, hitting, and doing the kind of work that rarely made headlines but won games. In the fourth quarter, Steve Van Buren plowed into the end zone for the only score. Eagles 7, Cardinals 0. Philadelphia’s first NFL championship.

In the pre-Super Bowl era, this was the game. A one-and-done title matchup that decided everything. For that generation of Eagles fans, those championships were their Super Bowls long before the word existed.

A year later in Los Angeles, the weather flipped from snow to driving rain. The field turned to soup as the Eagles met the Rams for a second straight title. In the second quarter, Pihos slipped behind the defense and caught a 31-yard pass for the only offensive touchdown of the game. The Eagles won 14–0. Another shutout. Another championship.

By 1948, his 766 receiving yards and 11 touchdowns ranked second in the league. All-Pro honors and Pro Bowls followed. Pihos later said of Van Buren in that era, “Steve was hell on a leash. His stamina was unbelievable. How he kept going in those conditions, I’ll never know.” Years afterward, he summed it up simply. “When I joined the team, we started winning. When you win, everything is great.”

Those back-to-back shutouts in 1948 and 1949 stood as the franchise’s last football championships for 57 years, until the Eagles finally lifted the Lombardi Trophy in Super Bowl LII after the 2017 season. When the Eagles list their championships today, 1948 and 1949 remain the foundation. Pihos’s fingerprints are all over them.

Slump, Stubbornness, and the Triple Crown

Then football did what it always does to great players. It tested how much more they had to give.

In 1952, after years of playing both offense and defense, Pihos’s receiving numbers plunged. The Eagles used him mostly at defensive end. He caught only 12 passes and scored once. The whispers followed. Maybe he was finished. The front office asked him to take a pay cut and stick to defense.

For a son of Greek immigrants who had buried a father, stormed beaches, and clawed his way into the NFL, that sounded too much like being told to fade quietly. He refused. That offseason, he trained in silence.

From 1953 to 1955, he answered. Pihos led the league in receptions three years in a row, catching 185 passes for 2,785 yards and 27 touchdowns. In 1953, he captured the receiving Triple Crown, leading the NFL with 63 catches, 1,049 yards, and 10 touchdowns in just 12 games.

Later in life, he said, “I never dropped a pass, period. If they hit my hands, it was caught.” Ray Didinger, who studied his film, didn’t argue.

In November 1955, Pihos quietly announced he would retire at season’s end. Years earlier, he had run into Joe DiMaggio in Atlantic City. DiMaggio told him to retire on top. Pihos listened. In his final regular-season game, he caught 11 passes for 114 yards, then scored the East’s first touchdown in the Pro Bowl on a 12-yard grab.

Nine seasons. One missed game. Two championships. Six Pro Bowls. Three straight seasons leading the league in receptions. A Triple Crown.

Number 35 and a Greek Legacy

When Pihos walked off the field for the last time, he left more than numbers. He left a legacy woven into Philadelphia sports history and into one number.

In this city, 35 still points back to him. He wore it for every game of his Eagles career, including those championship seasons. Long before jerseys became brands, he made that number stand for something. Reliability. Physicality. Presence. The idea that a Greek surname could sit comfortably at the center of Philadelphia sports history.

For Greek American families who worked diners, bakeries, and corner stores, that mattered. They could open the newspaper, point to his name, and tell their kids, “That one? He’s one of us.”

In 1966, Pihos was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame. In 1970, he was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton. His presenter, former teammate Howard Brown, echoed Bo McMillan in calling him the most complete player his coach had ever handled. Vice President Spiro Agnew sent a note praising his durability and drive. At the podium, Pihos kept it simple. “This is the fourth quarter,” he said, “and it’s the first time in my life I didn’t have to worry about a two-minute drill.”

Greektown, Locust Bar, and a Name in the Air

For Greek families gathered around radios in South Philly kitchens and cafés near Eighth and Locust, those titles were about more than football. In a country that hadn’t always welcomed them, they could point to the city’s champions and say, “One of them is ours.”

Well into the 1970s, there was a visible Greek presence in old Philly Greektown. The Locust Bar, run by Nick Dinoulis at 10th and Locust, was a gathering place for Greeks, Greek Americans, and locals swapping stories about life and the Eagles. Greek American attorney Chris Bokas remembers hearing about Pihos there, talking football with Judge Constantine “Gus” Shiomos and the regulars when the neighborhood was still vibrant.

They remembered that Pihos wasn’t alone. Quarterback Bill Mackrides, another Greek American, was part of those same championship teams. Greektown had two names to claim in the Eagles’ first dynasty.

“Dad was really proud of being Greek,” Melissa said. “He made that important to me, too.”

A Daughter, a Disease, and Keeping His Story Alive

In 2001, Pihos was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. The same mind that had processed defenses in an instant began to cloud. Melissa decided that if the disease was going to take his memories, it would not take his story.

In 2009, she created Dear Dad, an award-winning short documentary. Two years later, she premiered Pihos: A Moving Biography, a multimedia performance blending dance, film, and archival footage. The work toured multiple cities as a benefit for the Alzheimer’s Association. On stage, dancers embodied his father’s murder, his wartime service, the violence and beauty of football, and the slow disintegration of memory. Melissa returned to Orlando, dug through records of Louis’s killing, and turned pain and inheritance into movement.

“That’s one of my missions,” she said. “He was so good to me.”

The production included interviews with former teammates, broadcasters, and doctors. They spoke not just about a Hall of Famer, but about a man trying to hold on as the disease advanced.

Below is Dear Dad (2009), Melissa Pihos’s short documentary exploring her father’s life and Alzheimer’s diagnosis.

Pete Pihos died in August 2011 at the age of 87. Alzheimer’s took his words, but it did not erase the story he had already written into two communities, Eagles fans and Greek Americans.

In 2020, in a French forest, a woman found a set of dog tags Pihos had lost during the war. She tracked down Melissa and sent them across the ocean. When Melissa held them, she cried. For a family whose journey had passed through Orlando, Chicago, Bloomington, Philadelphia, and Europe’s battlefields, it felt like a quiet message. Remember him properly.

“I think people get caught up in his stats,” Melissa said. “But I think he’d want to be remembered as a good father, a good person, and someone who served his country.”

Today, when Greek American kids in the Philadelphia area pull on Eagles jerseys, most don’t know every detail of his life. But when the Eagles celebrate their early championships, Pete Pihos’s name always returns. Philadelphia’s Golden Greek carried his parents’ sacrifice, his community’s pride, and his city’s hopes onto muddy fields and snow-covered turf, then left it all there every Sunday, in the number 35.

Featured image: Pete Pihos during his early years with the Philadelphia Eagles, circa late 1940s.

Cosmos Philly is made possible through the support of sponsors and local partners. If you’d like to become a sponsor or promote your business to our community, get in touch.