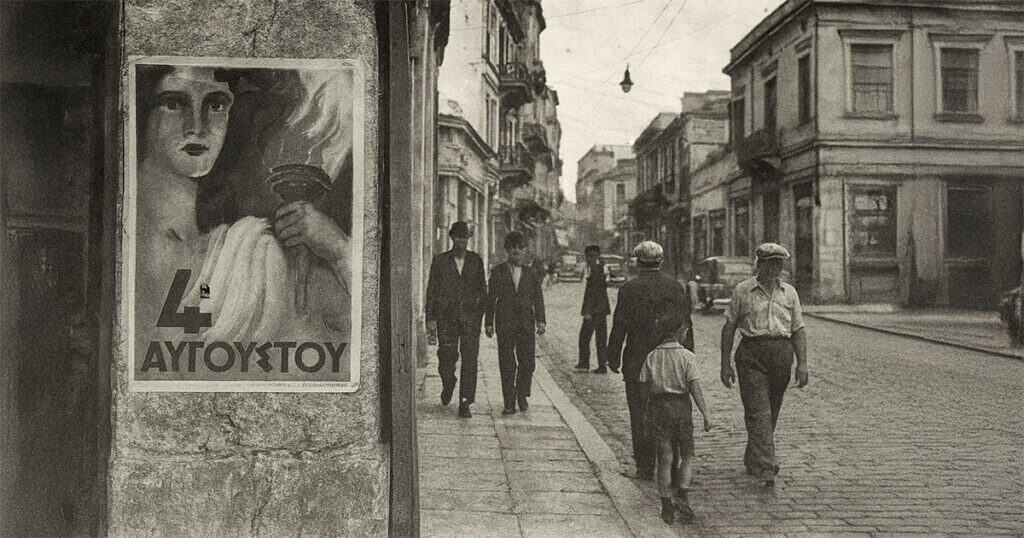

In choosing the title, “Skopje 2014,” I am referring not to the costly, kitsch Vegas-on-the-Vardar reconstruction of downtown Skopje, but rather the state of the Slav Macedonian state in 2014. This country is in existential peril and this serious and unfortunate situation merits our close attention.

Greece and FYROM (Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia) are at odds over the name of the state and the question of whether a separate nationality exists in FYROM or elsewhere calling itself “Macedonian.” The issue then extends to ownership of Ancient Macedonian history and provocative claims to Greek Macedonia.

But Greece is not FYROM’s real problem, its identity and demographics are the problem. Albanians make up well over 30 percent of the population, with a birth rate far higher than Slav Orthodox Macedonians. In 1999, using a borrowed air force from NATO, the Albanians succeeded in ripping Kosovo away from Serbia. Just a couple of years later, the Albanians in FYROM rose in rebellion and all Orthodox countries, Greece included, jumped to Skopje’s aid, and Greek peacekeepers patrolled in FYROM. The Ohrid Agreement, signed in 2002 to end the hostilities, basically turned FYROM into a joint state, Slav and Albanian, with the Albanian language having equal status as Slavomacedonian. The clock is ticking.

It has been over 10 years since the Ohrid Agreement, and the percentage of Albanians only grows as more and more Slavs leave the country for the large diasporas in Europe, North America, and Australia. Sometimes Slav Macedonians take Bulgarian nationality offered to any Slav Orthodox inhabitant of FYROM (Bulgaria claims that Slav Macedonians are really Bulgarians, and until the 1940s most people in the area self-identified as Bulgarian, which is now conveniently forgotten in FYROM’s national mythology). While the economy improved in the early years of 2000s, mostly due to Greek investment and growth of the Greek bubble economy, all has once again collapsed. FYROM has always had over 25 percent unemployment and a per capita income one fourth that of Greece. Corruption and cronyism are rife; all economic activity is politicized and ethnicized.

Then there is the issue of Slav Macedonian identity. As is often the case in the most existential of times, particularly in this part of the world, the leadership became more, not less, provocative and nationalistic. The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (VRMO) won the election over the more moderate Slav party, and upped the rhetoric on Greece even as Albanian coalition partners grabbed key seats, including [!] the defense ministry. Prime Minister Gruevski, whose grandfather fought and died for Greece in Second World War, is at the forefront of a much harsher line on the name issue, backed to the hilt by diaspora cliques in Toronto and Melbourne. Whereas in the past most Slav Macedonians readily admitted no relation to the Ancient Macedonians, new official history now claims more or less direct ties with Alexander the Great, to the disdain of most academics, even in Skopje. Many now refuse to call themselves Slavs at all, seeking to distance their identity from Bulgarians and Serbs. Notwithstanding, more and more Slav Macedonians are rediscovering Bulgarian, Serbian, Vlach or Greek roots, even as the Albanian bloc grows.

Gruevski was the main impetus behind “Skopje 2014,” a megalomaniacal, bombastic plan to facelift Skopje with buildings, statues, and monuments of all styles (most recently there is talk of doing a replica of Rome’s Spanish Steps). This in a country at the edge of financial and political collapse. Best known is the giant kitsch statue of Alexander the Great, but they have also built neoclassical, Byzantine, and even baroque buildings to celebrate the glory of their threadbare state. Most unbiased critique has been negative about this massive construction project and local opposition figures remind us of the state of the economy and that most contracts were sweetheart deals.

In the midst of hard line politics, the EU has expressed frustration with FYROM’s increased nationalism, authoritarianism, and her simmering internal troubles. Greece and Bulgaria, as EU members, are sure to block the present FYROM regime’s EU application. Bulgarian nationalism is growing and many Bulgarians actively look for FYROM to fall apart in order to gain land and a population Bulgarians always claimed as theirs. Daily ethnic incidents between Slav and Albanians are deliberately downplayed but the economy is deteriorating and to think that the current state of FYROM is sustainable is to be delusional.

What Could Happen?

Virtually anything could set the spark. A fight at a soccer game, a political rally gone wrong, a confrontation at a church, mosque in any city or town with an ethnically mixed population, could set things off at digital Twitter/Facebook speed. FYROM’s army is tiny, ethnically mixed, with an Albanian Minister of Defense. Kosovo and Albania are next door and have porous borders over which guerillas could easily infiltrate. Within hours or days the country could be divided roughly west to east along the line of the Vardar (Axios) River, with enclaves elsewhere. This roughly corresponds to where Albanians have local majorities. The southern part of the country along the Greek border will likely remain in Slav hands, and Skopje itself will likely divide along ethnic lines. The Albanians will likely take as much land as possible to establish a fait accompli, and then be prepared to bargain out some of this land in a settlement.

And Then What?

After neglecting this part of the world, once again it comes to center stage. There will be calls for intervention, but who would intervene, either for humanitarian reasons or to try to stitch this “Humpty Dumpty” of a state back together again? The FYROM Albanians are likely to have been emboldened by Kosovo’s declaration of independence to try something similar. The most powerful military in the immediate border is Greece, but it is altogether likely that the Slav Macedonians might characterize any Greek intervention as an invasion of conquest. The same goes for the Bulgarians, who, unlike the Greeks, do have a latent territorial claim to parts of FYROM. Most importantly, Turkey may want to step in the fray, acting both as an “honest broker” having good relations with the Albanians, who are overwhelmingly Muslim, and with the Slav Macedonians, whose national aims they support vis-a-vis both Greece and Bulgaria. Also, there is a small Turkish minority in FYROM they can claim to support and to protect.

The prospect of a Turkish base in FYROM, to the rear of both Greece and Bulgaria, is terrifying. It would also likely result in a permanent Turkish presence there, because, as we know, when Turks occupy a place, they usually stay. It would also likely result in a de facto division of the country into a Greater Albania and a rump FYROM as a Turkish protectorate likely to be rabidly anti-Bulgarian and anti-Greek. The Turks would effectively control Greece’s road and rail corridor to Serbia, and therefrom to Central Europe, effectively giving Turkey control over Greece’s road access to Europe. From there Turkey could expand its political influence into a Greater Albania as well as Bosnia.

This is the worst case scenario, and likely Greece and Bulgaria would have to respond militarily to a Turkish attempt to re-colonize the Balkans and Russia would likely not remain idle. It is unlikely that Europe and America would stand for this either, particularly as Erdogan is increasingly less popular in the West. In order to forestall this, and a possible Greek-Turkish confrontation (or Russian intervention), NATO and the EU would probably intervene with rapid reaction forces (whatever is available) in a patch-together effort to separate warring parties and forestall outside intervention. With a throw-together peacekeeping/peacemaking force, they could probably do no more than stop the shooting war, and actually harden the lines.

Perhaps the international community would prevent the Albanian piece from declaring independence, and/or uniting with Albania and/or Kosovo. Perhaps FYROM will be like Cyprus, with a divided capital and a portion of its internationally recognized territory outside of its control. What is certain is that the state will become even more of a welfare case, dependent on its diaspora for a lifeline as well as the goodwill of its neighbors it can ill afford to upset. Bulgaria will likely press its claim for annexation, citing the large number of Slav Macedonians who have Bulgarian nationality. Whether the Slav Macedonians will accept annexation to Bulgaria is a matter of debate; it could cause its own mini-civil war, in fact. It is not impossible that stateless Slav Macedonians might launch their own liberation front, with support from the diaspora. Greece would not be unaffected.

Where does this leave Greece? The worst case is the Turkish incursion, or a low intensity insurgency affecting the region, including parts of Greek Macedonia. Even absent this scenario, FYROM’s breakup would be a cause for worry. A larger Albania is not at all in Greece’s interest, and certainly a war to our north would be a humanitarian disaster which Greece should care about. Further, Greece has considerable investment in the region that would suffer, and the Thessaloniki-Belgrade corridor is vital to the Greek economy. Watch this space. Like everything else concerning FYROM, “it’s complicated.” Let’s not forget, also, that 2014 is the centennial year of a world war that started in the Balkans.