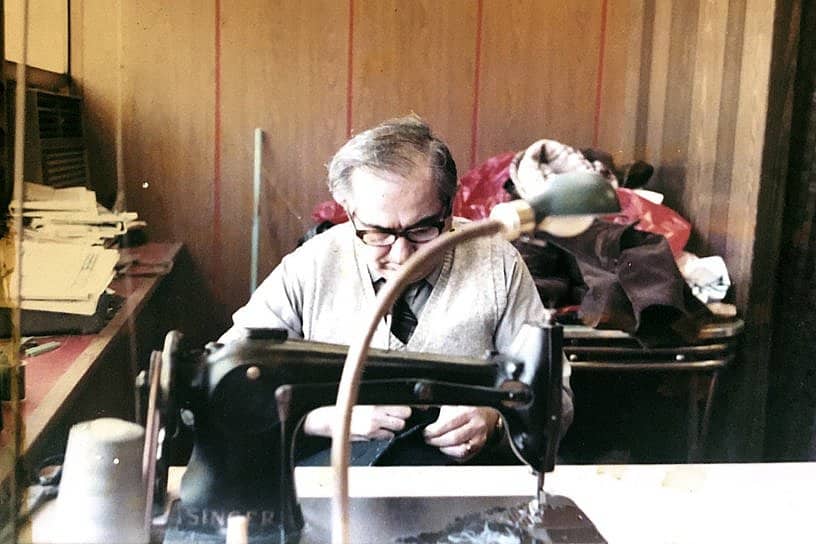

This is a picture of my dad, John Kazantzidis, or Vanias as so many of his friends knew him, and simply John the Tailor, as his customers referred to him. I was asked to describe this picture, when it was taken, where it was taken, and what was going on. Honestly, I can’t even place a date on it because no matter how far back I go, this is always how I remembered him.

While most Greek fathers had pizza stores or hot dog carts, my dad was a tailor. I used to be embarrassed that we didn’t own a pizza store, but as I grew older, I realized what a special skill this was and how this profession afforded us a life to be envied.

John the Tailor was located on 6840 Market Street, Upper Darby, above the landlord’s bar. Next to it was McDonald’s, Arrow Restaurant, and the Tuxedo shop on the corner. My dad shared space with the Pan-Macedonian Society and Lianidis Travel on the second floor. He served the patrons of the men’s stores on 69th Street for over thirty years, with customers coming from as far as Bala Cynwyd and Philadelphia. My dad was fast and precise. As a Virgo, he was a perfectionist; no man, woman, or child, would leave with ill-fitting clothes.

He had a bird’s eye view of the 69th Street terminal, and he could see everything. When I used to come home from school or head to my father’s store to pick up some money for Saturday shopping on 69th Street, it would not be a good sign if I saw my dad at the window. It meant he wasn’t busy. However, there were other times when he was so swamped, I would walk in with my friend Maria, and he would see me and say, “Ohhhhh, this is my daughter, love of my life,” hand me a twenty bill and shoo me away. On Monday mornings, I remember that there would be a stack of cash in the drawer by his bed.

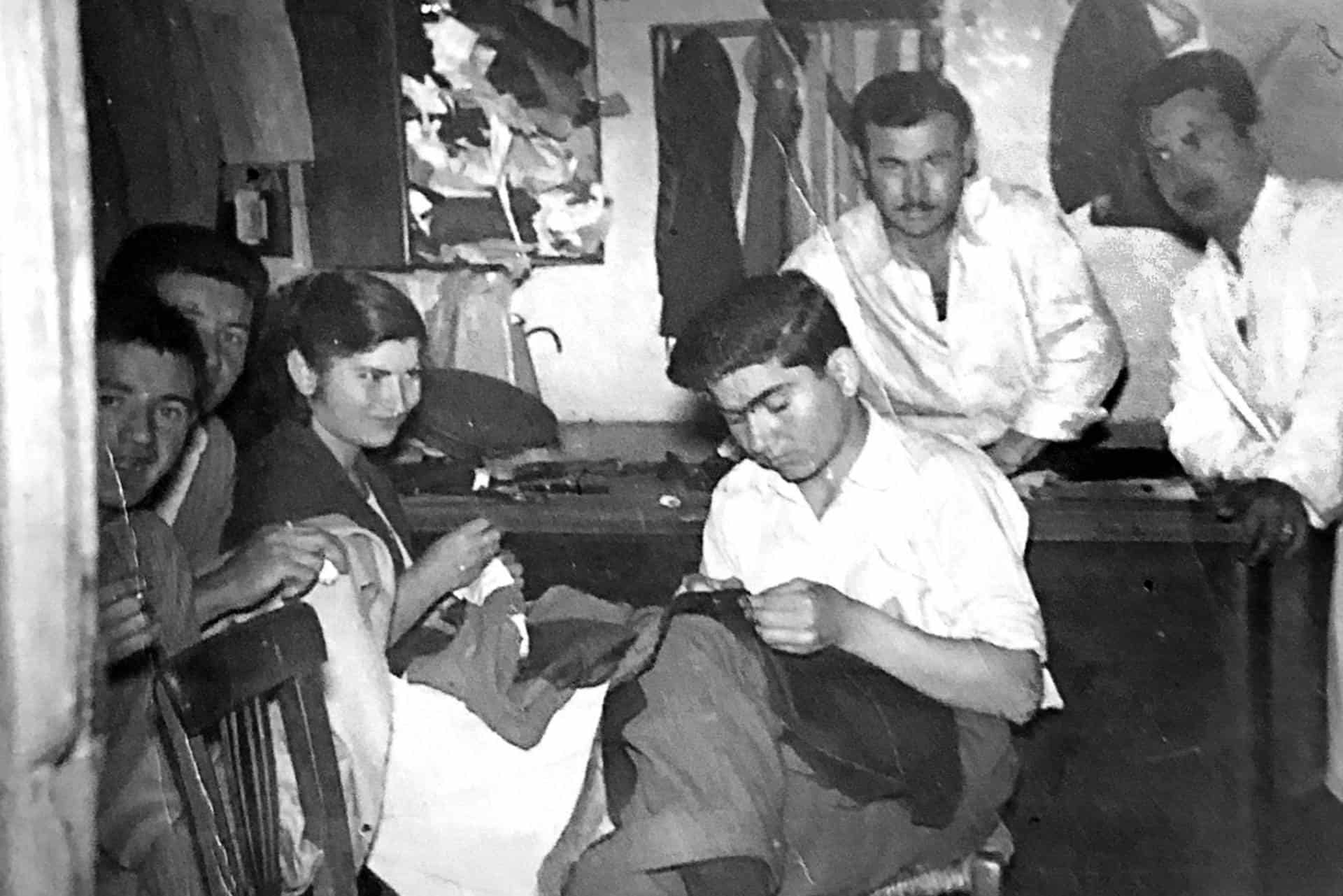

When he first came to Upper Darby, from Katerini, Greece, he really did think he died and went to heaven. He already lived as a refugee when the Pontians were exiled from Turkey. He was born in Sokhumi, Georgia, a former Russian Republic. Eventually, his family made their way to Greece, where they endured extreme poverty. I will never come to know the poverty, God willing, and then entered adulthood facing still tumultuous times in Greece. All those Greek immigrants who came to the United States in the late 1960s and early 1970s sought economic opportunity and relief from the junta. As desperation and despondence set in, my dad made the United States’ journey alone, ending up in Astoria first, with a measly twenty dollars to his name. Very soon after, he made his way to Upper Darby, found a spot to set up shop, got a street-level apartment on Kent Road, and we joined him after I was born. They were right; the streets were paved in gold, as far as he was concerned.

My mother was heartbroken to leave her family, but he promised her a beautiful life. He was not wrong. Their aching hearts, missing their families back home, and the only way of life they ever knew, were easily comforted by cash, and lots of it. My dad used to come home on Saturdays and count his earnings, and my mom used to say to him, “Vania, did you rob a bank?” My dad would chuckle, and say, “I love America, vre.” Saturdays my dad would also come home with bananas because they did not have them in Greece. We had bananas to our heart’s content and KitKats chocolates from the Vasiliadis’ bakali, up the street from the store. After dinner, he would head out to pull all-nighters with all the other Greeks at Ceasar’s Kafeneio, play cards, talk politics, and watch soccer. It certainly was a beautiful, care-free life.

We were so fortunate; we got to visit Greece, literally every summer. We would go back with suitcases full of sheets, towels, Kool-Aid, and clothes that I would always leave behind for my girl cousins. Maybe we liked to impress the family back home with our good fortune? I am certain so many of you reading this can attest to this experience, as shared by so many.

I vividly remember how much he loved his job, this country, and how he called all his male customers “brother,” and all the females, “sweetie.” Without knowing a lick of English, he managed to win his clients’ hearts by using these terms of endearment that made him so popular and loveable. The thick Greek accent made it even more flattering. Even when they left, he would say, “Have a Nice Day” and “God Bless America!”

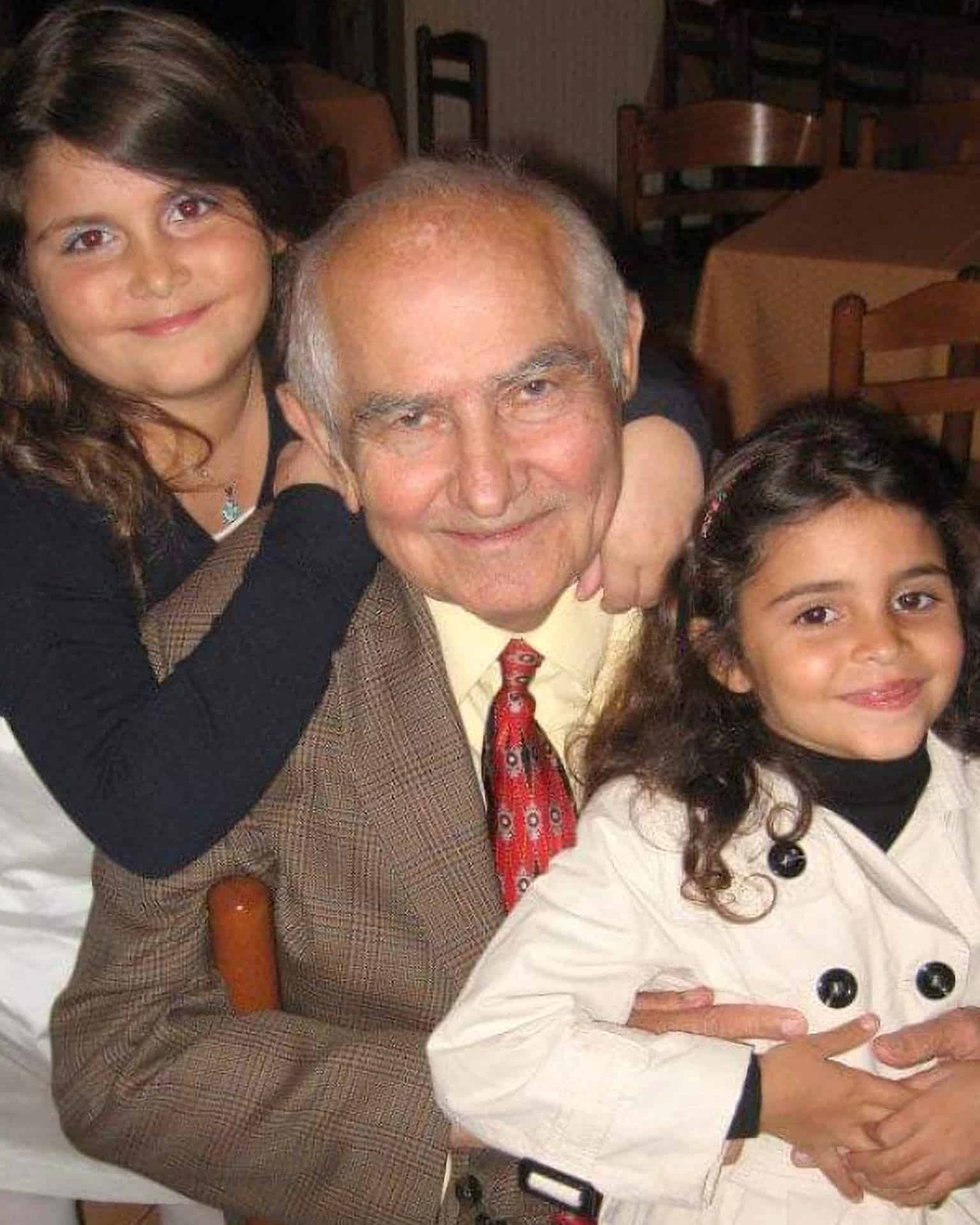

All good things come to an end. Sadly, my father moved on to the other realm, but what he left me were amazing memories and life-lessons. A man with only a 6th-grade education taught me more than any professor I’ve had. His generosity towards me has now passed down to my own children. They got to know Pappou Vania, and adored him. He used to say. “Effie, I have life lessons,” and I would roll my eyes. Now those life lessons serve my family and me.

My father’s venture was not singular. So many Greeks built strong foundations for their families and are pillars supporting the younger generations. We might not all live in clusters around St. Demetrios anymore, but the influences can be seen in any local church. Young families that I grew up with, now with our own children, continue to preserve our Greek culture and heritage so it will not be lost, hoping that we can be as good parents as they were. The Greek community is still strong, the Greek presence is still solid, and I wouldn’t want to be anything but Greek.

This story started as a few sentences describing where and when this picture was taken, but the story behind this picture was so sacred and complex, I could not help but share. I hope this has brought you back to memories of your own parents and stories they have told. God Bless America, thank you God and thank you to my parents for all the blessings I have received. Amen.