President Harry S. Truman established with the Truman Doctrine, that the United States would provide political, military and economic assistance to all democratic nations under threat from external or internal authoritarian forces. The Truman Doctrine effectively reoriented U.S. foreign policy, away from its usual stance of withdrawal from regional conflicts not directly involving the United States, to one of possible intervention in faraway conflicts.

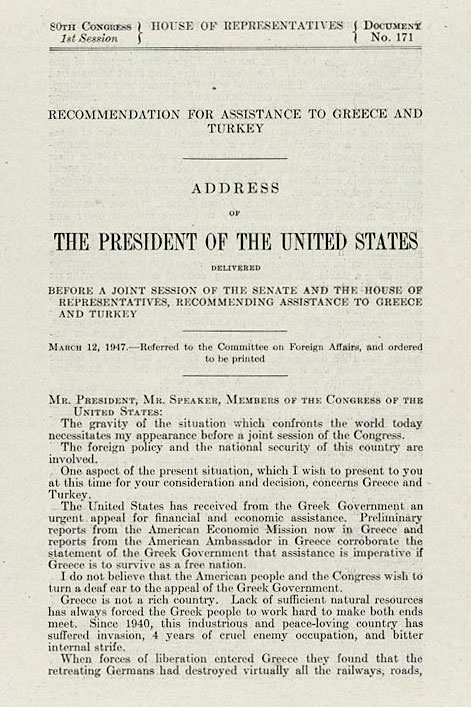

The Truman Doctrine arose from a speech delivered by President Truman before a joint session of Congress on March 12, 1947. The immediate reason for the speech was a recent announcement by the British Government that, as of March 31, it would no longer provide military and economic assistance to the Greek Government in its civil war against the Greek Communist Party. Truman asked Congress to support the Greek Government against the Communists. He also asked Congress to provide assistance for Turkey, since that nation, too, had previously been dependent on British aid.

At the time, the U.S. Government believed that the Soviet Union supported the Greek Communist war effort and worried that if the Communists prevailed in the Greek civil war, the Soviets would ultimately influence Greek policy. In fact, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had deliberately refrained from providing any support to the Greek Communists and had forced Yugoslav Prime Minister Josip Tito to follow suit, much to the detriment of Soviet-Yugoslav relations. However, some other foreign policy problems also influenced President Truman’s decision to aid Greece actively.

In light of the deteriorating relationship with the Soviet Union, and the appearance of Soviet meddling in Greek and Turkish affairs, the withdrawal of British assistance to Greece provided the necessary catalyst for the Truman Administration to reorient American foreign policy. Accordingly, in his speech, President Truman requested that Congress provide $400,000,000 worth of aid to both the Greek and Turkish Governments and support the dispatch of American civilian and military personnel and equipment to the region.

Truman justified his request on two grounds. He argued that a Communist victory in the Greek Civil War would endanger the political stability of Turkey, which would undermine the political stability of the Middle East. This could not be allowed in light of the region’s immense strategic importance to U.S. national security. Truman also argued that the United States was compelled to assist “free peoples” in their struggles against “totalitarian regimes,” because the spread of authoritarianism would “undermine the foundations of international peace and hence the security of the United States.” In the words of the Truman Doctrine, it became “the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.”

Truman argued that the United States could no longer stand by and allow the forcible expansion of Soviet totalitarianism into free, independent nations because American national security now depended upon more than just the physical safety of American territory. Rather, in a sharp break with its traditional avoidance of extensive foreign commitments beyond the Western Hemisphere during peacetime, the Truman Doctrine committed the United States to actively offering assistance to preserve the political integrity of democratic nations when such an offer was deemed to be in the best interest of the United States.

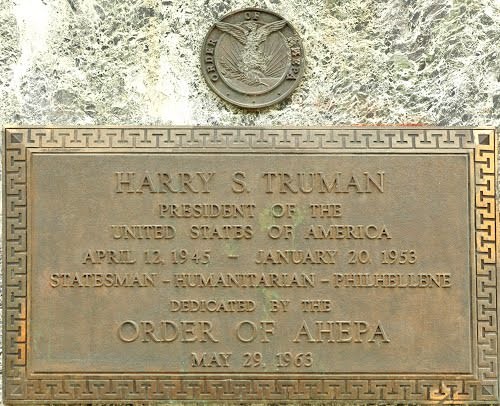

The Order of AHEPA honored Brother Truman for his assistance to Greece and erected a statue in his honor in Athens in 1963.