The Treaty of London, signed by the belligerents in May 1913, ended the First Balkan War. The Balkan League, an alliance of four Balkan Orthodox states, had crushed the Ottoman Empire and sent the borders of Turkey in Europe to the Chatalja Lines, just outside of Constantinople, and the Gallipoli Peninsula, which would become infamous a few years later.

The allies had scored a stunning victory, one rather unexpected in the chancelleries of Europe, which expected an Ottoman victory and a return to the status quo ante. The allies each greatly increased their size and population, though they also gained large minorities and their ideal claims now overlapped. No country was particularly satisfied with their gains, and the Great Powers, moreover, added fuel to the fire by establishing Albania out of Greek- and Serbian-occupied territory, and rival powers backed rival clients in the Balkans.

Aside from a few Turkish and Albanian irregulars, the peninsula belonged again to the Balkan people, after 500 years. Roughly speaking, the zones of occupation divided in such a manner. Bulgaria held all Western Thrace, most of Eastern Macedonia, and Eastern Thrace minus Constantinople and Gallipoli. The Treaty of London drew a line in Eastern Thrace between Enos on the Aegean Sea to Midia on the Black Sea, and everything west belonged to the Balkan League. Serbia held nearly all of what is today FYROM, Kosovo and Northern Albania. The Sanjak of Novi Pazar, once again an area of Muslim volatility, was split between Serbia and Montenegro and basically constitutes the present Serbian-Montenegrin frontier. Greece gained Epirus (Southern and Northern Epirus), Western and south central Macedonia (including, of course, Thessaloniki), and all of the Aegean Islands except those under Italian rule (Rhodes and the Dodecanese Islands). Crete’s union with Greece, proclaimed at the outset of the war, was formally recognized. But this situation was far from stable.

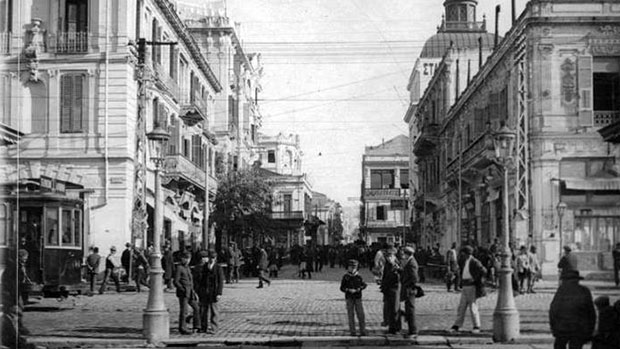

Any hopes from earlier in the conflict that a new “Byzantine” Great Power would emerge, or perhaps a Russian-dominated Balkan federation was dashed away. Bulgarians were behaving abominably towards Greeks in their numerous areas of control in Macedonia and Thrace, and in Thessaloniki their joint occupation force acted as co-conqueror. Clashes between Greeks and Bulgarians in the city, particularly with the tough Cretan gendarmes, increased in intensity. Elsewhere incidents abounded along the frontiers of occupation. Serbs were having similar problems with the Bulgarians, and the Bulgarians showed little appreciation for the Serbs’ aid in the capture of Adrianople, which was an act of kindness with no Serbian interests served save those of a common alliance. Moreover, the Slav Macedonians in the Serbian zone of occupation were more oriented towards Bulgaria, and the Bulgarians actively encouraged their discontent.

Events were moving quickly to a showdown. Bulgaria had the largest and strongest army in the Balkans, and their stunning victories fueled the arrogance that is never far from the surface in any (and I mean any) Balkan nation. Greece and Serbia had few overlapping claims, and both in general respected the agreement that the border would become where the armies met. Naturally, the two nations grew closer together, and Russia began to favor Serbia over the other Slavic “Little Brother,” Bulgaria. The Turks, too, were well apprised of the situation and nursed hopes of pushing back the frontiers to protect Constantinople, within range of Bulgarian siege guns. Romania also surveyed the situation from beyond the Danube. A Balkan fratricide needed only a spark.

It was not long in coming.