Few events could have been more important in the road to Greek national agency than this treaty in 1774 which ended the Russo-Turkish War. The war itself had been devastating for Greeks, but the peace laid the groundwork for a fundamental change in calculus, which helped to birth the Greek state, and the formed the foundation for the Greek merchant marine to this day. It is no exaggeration to say that this treaty changed the course of history.

Most Greeks will remember this Russo-Turkish War because of the Orlov Rebellion, an ill-advised attempt to create a second front in the Peloponnesus to draw Turkish troops away from the Black Sea theater. The rebellion received scant serious Russian support and suffered from considerable dissent and disorganization in the Greek ranks—an all-too-common Greek problem. The Turks drew in Albanian Muslim militia which devastated the Peloponnesus for years to come, and many Greeks fled the peninsula, often ending up in the newly-conquered Russian Black Sea coast, where they bolstered old Greek communities and they actively worked in rebuilding a region devastated by decades of warfare between the Russians and the Turks.

Like the Austrians several decades before, the Russians actively sought Balkan Orthodox immigrants from the Ottoman Empire to develop the lands taken from the Turks. They were aware that these Greeks and Serbs had an axe to grind with the Ottomans, and their military and commercial skills were welcome. In the southern zone of the Austrian Empire, Serbian soldier-farmers kept the frontier safe, and Greek and Serbian merchants actively worked in developing the Austrian economy. The Russians, drawing on this example, actively recruited Serbian, Greek, and Bulgarian colonists. They also had the advantage of a common Orthodox religion with the Russians.

The key provision of the Treaty that changed conditions for the Greeks was the ability for Orthodox Christian subjects of the Ottoman Empire to fly the Russian flag on their merchant ships. This suddenly provided the ships of the actively growing Greek merchant fleet to have extraterritorial protections in the Ottoman Empire. As the Russians set to bringing the fertile Ukrainian steppe to the plow (often with Balkan Orthodox farmer-immigrants), they basically “subcontracted” their huge export trade of bumper crops to the Greeks, who could fly the Russian flag. This put the Greek merchant fleet into overdrive, as island shipyards hummed with activity and large Greek merchant houses in Constantinople, Smyrna, Chios, and, increasingly in Diaspora centers such as Trieste plowed money into shipping.

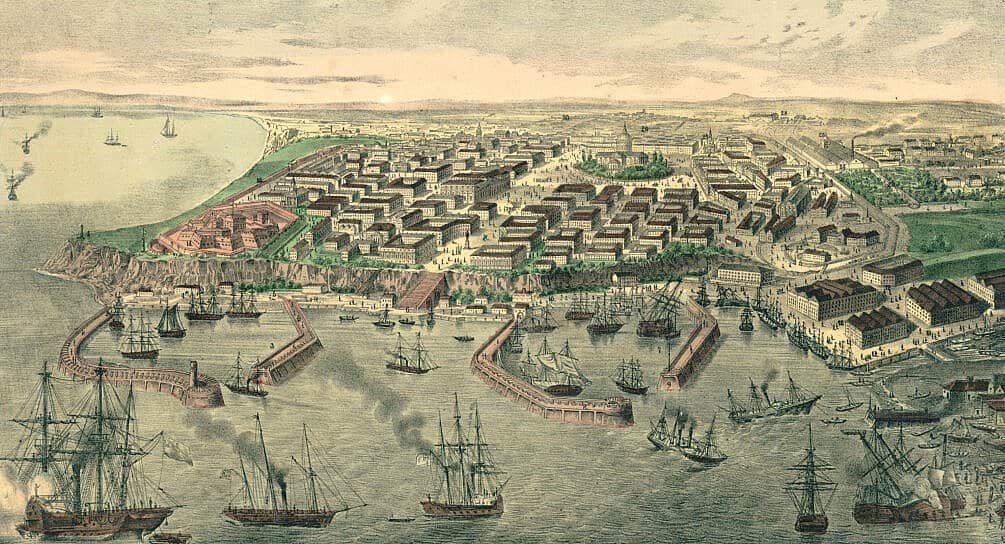

Founded near an ancient Greek port, Odessa thrived with a multiethnic buzz, as Greeks, Bulgarians, Jews, Italians, Serbs, Germans, Poles, Ukrainians and Russians wheeled and dealed in a boomtown that rested on the back of this 1774 treaty. Large local fortunes were being made, often by Balkan immigrant entrepreneurs, but thoughts of home were never far from mind. Thus, as Greeks actively pursued opportunities and served loyally the Russian Tsar, who was, after all, a coreligionist, they still yearned for an independent homeland.

Goods and money were not the only things that flowed. In 1814 three Greek merchant-clerks formed the Philike Etairia (the Friendly Society) a secret organization built on Masonic principles dedicated to the liberation of Greece. From the Diaspora, the membership of the Philike Etairia slowly grew to other locations in and out of the Greek Homeland, carried in the hulls of Greek ships which were a mobile central nervous system for this increasingly wealthy diaspora that sought not just economic, but national agency.

In 1821, the first shots of the revolution were fired, not in the Greek homeland, in the province of Moldavia (now part of modern Romania), which formed the border between the Russian and Ottoman Empires. Russo-Greeks, many of them officers on a leave of absence from the Russian military, stormed across the border where they were eventually defeated by the Turks. But further south, in the heart of what became modern Greece, the Revolution took hold, and while the Russian government maintained an official hostility to the Greek Revolutionaries, Greco-Russians did get involved either financially or personally, in the struggle.

Eventually the Russians, like the British and French, did intervene in the Revolution, sealing the deal and Greece got her independence, of a sort. The Greek commercial presence in Southern Russia continued, bolstered by waves of Pontic Greeks fleeing the Turks. The grain of the Ukrainian steppes was gold to several generations of Greek merchants and shipping, and these Russian subjects readily fought for their sovereign bravely, even as the Russians rarely advocated for Greek interests. These Greco-Russians continued to serve Russia and later the Soviet Union loyally, despite Stalin’s purges, and many made their way back to Greece after the fall of the Soviet Union.

The Russo-Turkish war of 1770-1774 cost the Greeks dearly, yet they managed to salvage much from the wreckage. The Russians did not do us any favors; they needed the Balkan peoples’ brains and brawn in their new frontier province, and Greeks specifically to carry on their foreign trade. However, the Greeks and other Balkan peoples succeeded both personally and in building foundations for their future states. The Greek merchant mariners piloted the waves of international politics with the same savvy as the seas; pity the Greek state has rarely shown the same acumen.